Rio not so grande

By Michael Roberts

"Well, killing a man isn't clean and quick and simple. It's bloody and awful. And maybe if enough people come to realize that shooting somebody isn't just fun and games, maybe we'll get somewhere."

~ Sam Peckinpah

In the early1970’s, as a resurgent American cinema luxuriated in a glut of revisionist westerns, the man who had reignited the form with his visceral The Wild Bunch just a few years before, took another perspective and applied a neo-realist palette to the genre, producing the downbeat, anti-elegiac Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid. Peckinpah owed a debt to his mentor Don Siegel, who had encouraged him to learn his craft in routine television westerns like Gunsmoke and The Rifleman in the late 1950’s and followed his friend into feature films with his debut, the routine but gritty western The Deadly Companions in 1961. Peckinpah then wrote the first screenplay for, and nearly directed, Marlon Brando’s One-Eyed Jacks, but fell out with the mercurial star, who then proceeded to alienate the next prospective director, Stanley Kubrick. One-Eyed Jacks was in fact Peckinpah’s first attempt at the Billy the Kid story, over a decade before he finally shot his own version, in the interim he’d made a mark in features with other westerns, the reflective, fin de siècle of Ride the High Country in 1963, the sprawling and rugged Major Dundee, and the masterful, if spectacularly bloody, The Wild Bunch.

Billy The Kid (Kris Kristofferson) and several of his henchmen are killing time in New Mexico when his old friend, Pat Garrett (James Coburn) rides up. Pat informs the Kid he is becoming a lawman in a few days and will have to run the gang out of the territory. Garrett returns with a posse and a gunfight ensues, Billy is captured and put into the Lincoln County Gaol. After a brazen escape Pat spends months pursuing the outlaw, but turns down an offer to do so for money. A game of cat and mouse between the two begins, culminating in a showdown at Old Fort Sumner, where Garrett finally gets the drop on his old friend.

The laconic pace of the film affects an almost European, art house aesthetic, as Peckinpah offers a tone poem in place of a narrative driven western. After the visceral impact of The Wild Bunch, controversial for its graphic (for the time) slow motion violence, Peckinpah instead favours a lyrical approach that unlocks the poetry of the everyday, even of the mundane. Rather than deliver a forensic policieur, showing a lawman assiduously tracking down the villain, we experience a slow building mood piece laced with fatalism and melancholy, hardly the action packed sequel to The Wild Bunch that MGM demanded from the beleaguered director. Often called “elegiac”, the film actually de-romanticises the west, even as the surly director carved a mythology to challenge that of classicists like Ford and Hawks, and presents a place where boredom is as big a threat as a bullet and villains of all stripes stand around waiting for something to happen.

Peckinpah cues some subtle biblical allusions via the crucifixion pose Billy adopts upon capture, with Garrett the unmistakable Judas in black. The tenor of the fable is that of the cost of ‘selling out’, as Garrett struggles with a ‘respectable’ profession that is stultifying in comparison to the Kid’s freewheelin’ ways. Billy is a criminal and killer, but there is a purity in his actions as Peckinpah sees it, and Garrett’s alignment with corrupt ranchers and money grubbing politicians serves to make him a betrayer of the Kids ethos, “ain’t the same man”, Billy says dryly. Peckinpah bookends the film with the killing of each major character, starting with Pat’s murder years later and cutting back to Pat’s encounter with Billy, the unmistakable overtones being the former was Pat’s comeuppance for the latter. Pat’s self-realisation that he’s a sell-out is delivered in a devastating moment when he’s faced with his own reflection in a long mirror, and he ‘kills’ the man he sees in disgust. Coburg is never less than compelling as Garrett, investing the role with a weather beaten authenticity and subdued gravitas.

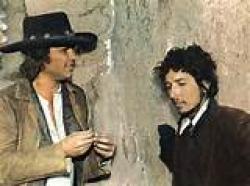

The opening for Peckinpah’s involvement in the film came when director Monte Hellman dropped out of the project, after having been attached to the film along with his Two-Lane Blacktop writer Rudy Wurlitzer. MGM were struggling to keep up with the nascent ‘youth’ market in the wake of the success of Easy Rider, and were talked into having the ‘cool’ Kristofferson as part of the package, then a star on the rise but in fact 14 years older than the 22 year old character he played. Peckinpah threw out the first script and re-wrote the piece with Wurlitzer, who wasn’t happy with the changes, and decided on casting singer-songwriter Kris Kristofferson as Billy, to appeal to the youth market. Kristofferson brought along his friend Bob Dylan, who was quickly signed up by Peckinpah to compose the soundtrack, and who provided the delicate centrepiece in the moody titular ballad, and in Knockin’ on Heaven’s Door, a song not found in the Directors original cut, but used in the final Special Edition in 2005.

The enigmatic Bob Dylan, in the middle of a supremely productive creative period not only scored the soundtrack but played the wanna-be gang member Alias, and graced the screen with a nervy presence and a memorable opening riposte when Billy asks him, “Who are you?” to which he replies “That’s a good question.” Touché. Peckinpah cast the film with several peerless cameos from a veritable rogue’s gallery of western character actors, the best of them being a casually vicious Chill Wills and an unforgettable and touching Slim Pickens, dying almost in the arms of his gun toting woman, Katy Jurado. Peckinpah didn’t use the song Dylan wrote for the sequence, but its restoration underlines how superbly Dylan underscored the moment, Kristofferson calling it “the strongest use of music that I had ever seen in a film. Unfortunately Sam had a blind spot there."

Sam Peckinpah battled his own demons as well as the fractured studio system of the day, meaning most if not all of his projects were ‘troubled’. Despite all his personal foibles he managed to conjure a fine legacy with several films full of insight, verve and edge, creating cinema that questioned the materialistic values of the modern world, in Peckinpah’s universe it was better a bad man with a code than a good man with none. Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid is a fine and atmospheric western, it succeeded despite its elliptical narrative and a slightly miscast ‘Kid’, its strengths more than compensating for any weaknesses, and its tone and realism elevated the genre and set a benchmark for any cinematic depiction of the era that followed.