Bresson remembers

By Michael Roberts

'Hide the ideas, but so that people find them. The most important will be the most hidden.' ~ Robert Bresson

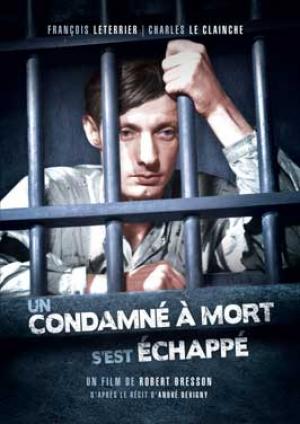

Robert Bresson’s A Man Escaped is a miracle of economy and a testament to Bresson’s singular vision in taking a stock situation like an escape film and turning it into a transcendent work of art. That something so poetic can also be so tense and involving merely puts other escape movies into stark relief, Bresson achieves a seemingly effortless verisimilitude with his techniques of under-stated ‘performances’ from his ‘models’ and a spare and almost documentary approach to the visuals. Investing time with the various dilemmas facing his lead character is a key device, in as much as he stays with the monotonous, repetitive process of digging out the wood from the door, of sharpening the spoon to use as a chisel, and this investment pays off later as the audience has invested emotion in ‘sharing’ the effort. It’s a technique Jacques Becker would use to great effect a couple of years later in the brilliant Le Trou, and where modern directors would cut away many times to other events these auteurs stick with the task, building our emotional investment subliminally in the process, thereby making the outcome more significant for the viewer. Bresson himself was imprisoned for a year under the Nazi’s and opens the film with a plaque that commemorates over 7000 French deaths at their hands in French prisons. It is a true story told ‘without embellishment’, a phrase that could sum up Bresson’s approach to cinema, and is based on the memoir’s of André Devigny, who escaped from Fort Montluc in Lyon in 1943.

The spare use of music in Bresson film’s again is a feature of A Man Escaped and the film opens with Mozart’s Mass In C Minor which is only re-introduced in a few sequences. In Vichy France Lt Fontaine (François Leterrier) is charged with blowing up a bridge as part of the resistance, he is sent to prison. He attempts to escape from the car during the journey, but is thrown into handcuffs and then beaten. His first cell is close to the ground floor and overlooks a courtyard, he exchanges messages with other prisoner’s who inform him that they can get letters sent to his family. Fontaine decides to trust the other prisoner’s knowing that any betrayal could lead to further punishment, but the men take the letters and also arrange for small objects to be passed to him that help with his new environment. Fontaine is taken to a new cell on a higher floor and later hears that men who had secretly slipped letters out of the camp had been found and executed. Fontaine gets into the routine of prison life, meeting a larger group from his area each morning to wash and clean up, and here he strikes up some friendships and plans with Orsini (Jacques Ertaud) to escape together. Using an iron spoon Fontaine starts to dig away at the wood on his door, realising that he will be able to shift the planks on it and get through. Eventually he gets out and finds access to the roof via a skylight, then slips back and waits for the right moment.

Orsini refuses to wait any longer, there is even talk that Fontaine is not serious and is stalling, that he is a ‘perfectionist’ and Orsini makes a break for it but fails and is caught. Orsini is executed and Fontaine is taken away to be told that his sentence is death, he’s led back to the prison not knowing if he’ll be put in the same cell where all the fruits of his hard work is or even when the sentence will be carried out. The prison is filling up and a young Frenchman, Jost (Charles Le Clainche) who had joined the German army is thrown in with Fontaine, who now has to decide if he kills him or takes him with him. Jost is seen being friendly with German guards during the morning routine and Fontaine again has to decide if he trusts him or not. Jost agrees to escape with Fontaine. Knowing he could be taken away at any time and shot Fontaine and Jost leave that night and climb out onto the roof. Fontaine has to kill a guard in the process, an event Bresson leaves to our imagination, and the two men eventually use their hand made ropes to climb across the walls to freedom.

The naturalism that Bresson evinces in every area, but especially with Leterrier gives the film it’s heart and soul. It’s impossible not to feel empathy with Fontaine’s loneliness and to feel every moment of despair when he loses people who have helped him survive his ordeal. Fontaine reaches out to his fellow human’s and decides crucially to trust in those when he needs to rather than descend into the abyss. The tools he has are his head and his hands, a priest says ‘God will save us’, Fontaine replies, ‘Yes, but he could do with some help’. Fontaine’s quest for freedom is an affirmation of reaching out to others, and if he didn’t have a second person helping he admits the escape would have faltered at the second wall. The guards are mostly not shown as complete people, often Bresson frames them from only the chest down, this gives a subtle suggestion that they are outside of the human community that Fontaine lives in, their presence an affront to a man’s basic human rights.

A Man Escaped is probably the most accessible Bresson, in that its structure, narrative and denouement flow in a fairly conventional manner, the similarity to other filmmakers stops there. Bresson ended up in class of very few, only some of the films of Bergman, Antonioni and Tarkovsky of the Europeans and Kurosawa and Ozu of the Japanese, amongst the classic directors can come close to that level of mastery, like a virtuoso musician who leaves a sonic fingerprint in what they produce. Bresson started as a painter, and his art is an accumulation of technique and of individual style, every frame designed to contribute to the overall hypnotic effect. The other great influence on his world view was his conservative Catholicism, but blessedly it doesn’t overwhelm his oeuvre, and his films can easily be interpreted in an existentialist way, even in a humanist fashion like that other great French classicist Renoir. Bresson won the Best Director award at Cannes in 1957 and this film marked him as an Auteur of the first rank, re-establishing his reputation 5 years after his superb last film Diary Of A Country Priest, and won him champions in the Nouvelle Vague, particularly Godard. Thankfully he continued to make astonishing, personal cinema for another 2 decades.