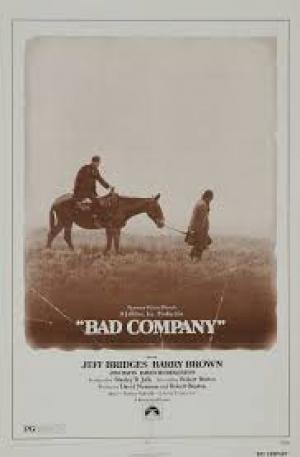

Benton, Bridges and Brown in the Badlands.

By Michael Roberts

After the late 1960’s fin de siècle aesthetic of Peckinpah’s The Wild Bunch and Hill’s Butch Cassidy and The Sundance Kid, the Western genre experienced a re-imagining via a series of ‘anti’ or revisionist Westerns and one of the finest of the herd was Robert Benton’s Bad Company. Robert Benton and David Newman had contributed significantly to the re-energising of American film in the wake of the Nouvelle Vague via their co-writing of the film that kick started the American Renaissance, Bonnie and Clyde in 1967. Benton again partnered with David Newman to write Bad Company and he also took the directing slot for what would be his debut. The tale of two young men heeding the Horatio Alger invocation to “go west young man” was astutely cast with a young Jeff Bridges in a pivotal early role and the ill-fated Barry Brown who shines as Drew.

Drew (Barry Brown) is a decent, Christian young man busy avoiding conscription into the Civil War by Union soldiers, leaving home with $100, a picture of his parents and his dead brother’s watch. He gets mugged by a gang leader Jake (Jeff Bridges), who takes the money and leaves Drew with a sore head. Drew is recovering at a minister’s house when Jake arrives trying to scam the minister’s wife, another fight occurs and drew recovers his money. Jake is impressed by his victim’s tenacity and invites him to join his gang, a situation that offers some protection in the wide open town. The gang decides to head further west but comes up against the harsh reality of living on the edges of civilisation where the law is mostly absent. The gang suffers many set backs, dodging several dangers and splits up for a time as Drew and Jake fall out again. Jake throws in with the vicious thug Big Joe (David Huddleston) and gets caught by the law, but Drew comes to his aid. Drew and Jake face an uncertain future together as they roam the barren land with no money and no prospects.

Benton presages the ‘odd couple’ era of buddy movies that arose post Butch Cassidy and The Sundance Kid, throwing together the seemingly opposing types of Drew and Jake but he was simultaneously harking back to the classic era of Mann-Stewart westerns, as he himself said, “I had conceived of Bad Company in the spirit of those Anthony Mann Westerns with Jimmy Stewart and Arthur Kennedy; you know, where the men were friends when they were younger, probably on the wrong side of the law, but now one of them has gone straight and the other has remained a criminal. Well, I wanted to do a kind of prequel, a movie about those same men when they were young. So when I cast Barry I was looking for a young Jimmy Stewart. However, when he (came in), he started talking about Montgomery Clift. I kept saying "Jimmy Stewart." He kept saying "Montgomery Clift." So I went to David Newman and said, "Here's the first important monologue the character has; write it so that if Daffy Duck did the part he would sound like Jimmy Stewart. David did a wonderful job, and when I gave the pages to Barry, he read them and said, "You've won." Now, I used to think that was an amusing story, but the truth is, I never really gave him a proper chance. With hindsight, my guess is he was closer to being right than I was.”

Benton unexpectedly raised the stakes of examining this bleak and threatening terrain by seeing it through the eyes of teenagers as they make their picaresque journey west, wide-eyed perhaps but not all that innocent. The dominant youth culture at the time of filming in 1972, enjoying media influence and real power via its opposition to the Vietnam War, were presented with a scenario that had some resonance to modern sensibilities. Young American men were dodging the Vietnam draft by their thousands, mostly heading north to Canada, so the opening scenes of the God-fearing Drew hiding from the Union soldiers enforcing the Civil War draft would have had a stinging resonance for the young men of draft age in 1972. The gang strikes out for the west because the draft has no legal standing in the Badlands, as yet unincorporated into any jurisdictions, but being on the edge of civilisation brings other risks.

Drew and Jake and their gang certainly battle the elements, but most of the threats come from each other or from other humans as much as from a harsh and unforgiving land. Their inexperience and trepidation is fuelled by fear and hunger and betrayal seems to be a constant companion to any group of travellers heading west. Benton sketches out a series of gritty vignettes, from the problem of skinning and cooking a rabbit to negotiating with a settler for the sexual services of his wife. Bandits are a way of life, roaming bands exploiting the paucity of law enforcement on the frontier, “If you’re gonna pull a gun on a fella you better fire it half a second after you do”, Jake is advised by the colourful and ageing outlaw Big Joe, who later says of himself “I tell ya boys, I’m the oldest whore on the block”. It’s an insightful and cynical acknowledgement as to his role as a faux celebrity in the eyes of burgeoning western mythology as he plays to the gallery.

Benton also sets the duality of the human experience, the battle between the ‘spirit’ or ‘soul’ with the earthy and corporeal. The two parts are seen in the religious Drew and the secular Jake, each transfixed and intrigued by the other. Drew writes in his diary “I have fallen in with some rough types” before bravely asserting, “I resolve never to do a dishonest act.” Drew reads excerpts from Jane Eyre to the gang each night around the campfire, hoping to impart some degree of culture to his companions but equally in an attempt to remind himself he comes from “good stock” and aid in his resisting the temptations Jake so readily succumbs to. Drew seems to wish that good breeding and culture might be some mystical protection or a bulwark between himself and the wild and unpredictable environment. Prior to robbing a bank Jake asks Drew, “How did that Jane Eyre turn out in the end”? “Fine, just fine” is the reply, as Benton ends on a note of ambiguity.

The New Cinema environment that had arisen on the back of the 1960’s counterculture scene fed a liberalism that helped to blow apart the staid and enervated US film scene and contributed to a re-thinking of that most American of forms, the Western. Benton explores a west that no-one had shone a light on prior during the plethora of western themed material since the dawn of cinema. The myth of the west as a man’s frontier where masculinity and effort bumped into a raw toothed nature and prevailed was revealed as propaganda in the extreme as Benton painted a decidedly grubby and ignoble canvas. Starvation and privation were more common companions to the migrating hopefuls, more likely to die from illness than from an ‘Injun’s’ arrow.

Robert Benton went on to win a slew of Oscars with his mainstream hit Kramer Vs Kramer a few years later, but for many his finest film will remain the modest but compelling Bad Company. Jeff Bridges went on to a stellar career as a Hollywood A- list player, albeit one still able to pick quirky and interesting side projects. Sadly the pressures of life proved too much for Barry Brown to cope with and he committed suicide in 1978, and Benton’s conversations with Brown about the tortured actor Monty Clift take on a different resonance in that light. Bad Company is no small legacy. along with Altman's stunning McCabe and Mrs Miller and Pollack's superb Jeremiah Johnson, it is the quintessential American Renaissance Western.