Ashby's farcical aquatic ceremony

By Michael Roberts

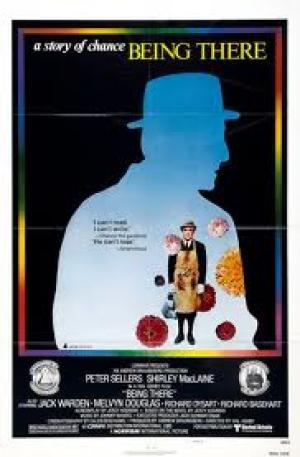

Hal Ashby was a Hollywood maverick who could only have existed in that environment during the broad-church era of the American Renaissance period of the late '60's and 1970's. Ashby's brand of energy and anarchy roamed freely across challenging concepts and liberal politics and was not an easy mix to keep in balance, but he constantly found interesting and engaging ways to express himself within the confines of a mainstream 'entertainment'. Peter Sellers championed the production of the film, a project he coveted since at least 1971, based on the book by Polish author Jerzy Kosinski, persuaded by Sellers to write the screenplay. Hal Ashby was Sellers' first choice for director, but his unhappiness with the Kosinski script led him to have his friend Robert Jones do some repair work that went un-credited. Jones had won an Oscar for best screenplay with Ashby's film 'Coming Home', the year before. Shirley MacClaine and Melvyn Douglas played the Washington power couple who befriend the mysterious Chauncey Gardener.

Chance (Peter Sellers) is a gardener and manservant at the residence of a wealthy old brownstone in Washington. The black Maid informs him that the old owner had died, and soon lawyers arrive to puzzle over his future. Chance has lived in the house since he was a child, never allowed to go outside, and has sourced his information about the world from radio and television. The yuppie lawyers don't know what to make of him, there is no record of him ever existing, and they evict him. Chance walks the streets of Washington, his benefactor's house in an area that has become little more than a slum. An accident involving a wealthy Washington socialite Eve Rand (Shirley MacClaine) sees Chance taken to the mansion for treatment, where her terminally ill husband, Washington kingmaker Ben Rand (Melvyn Douglas) befriends him. Chance gives simplistic homilies about life in the 'garden' that are interpreted by Rand and others as acute insight, and the sweet childlike demeanour that Chance delivers them with only heightens the impression. Ben is confronting his own mortality and reflecting on his legacy, and determines that the wise 'Chauncey' will be a key part of it.

Ashby plays the satire straight, and cuts deeper as a result, the visual formalism and elegant framing of the patrician world he's looking into only adds to the overall effect. The central concept of introducing a naive and innocent character with no discernable history into an environment where Machiavellian backstabbing is par for the elite country club course is a fraught conceit, but Sellers characterisation, in a career best performance, is the key that makes it work. The Zen like stillness that Sellers brings to the role creates a blank page for others to fill in what they need to see in 'Chauncey', and to hear what they want to hear from his innocuous sayings. Chance is the ultimate post-modernist character; he treats every piece of information equally and on face value. A televised Presidential meeting with the Chinese delegation is absorbed at the same level as an episode of 'Green Acres' or 'Sesame Street'. Classical music concerts and Loony Toons cartoons provide information in equal measure, and when Chance needs some indication of what to do when Eve jumps his bones, it's the love scene from 'The Thomas Crown Affair' playing in the background that provides the clues. This is a nice in-joke from Ashby, who edited that film for his mentor Norman Jewison, and it was for Jewison's, 'In The Heat Of The Night' that Ashby won a Best Editing Oscar in 1967.

Kosinski shows a deep understanding of the nature of politics, and lampoons the inherent hypocrisies mercilessly. Ashby's neat trick is to display Ben as a reasonable man, right up until his burial and the delivery of the eulogy by the President, which quotes some of his more crypto-fascist ideology, in the shade of an Ayn Rand or Masonic themed monolith. "I have no use for those on welfare", the President intones across his casket as Ben's right wing associates act as pallbearers and plot a succession plan for the Presidency. Ashby also pricks the nation's conscience on race, and emphasises the wealth divide between black and white, rich and poor. Chance leaves his home to the disco strains of Deodato's 'Also Sprach Zarathustra', a neat satire on Kubrick's '2001' birth of mankind scene, into a suburb of Washington that resembles a war zone, obviously having declined from a middle class neighbourhood in the 1920's to ghetto status in the late 1970's. Louise, the black maid sees Chance being feted on TV and exclaims to her shared house, welfare dependent friends, "It's for sure a white man's world in America".

Ben saw in Chance "admirable balance" and found him to be, "a very peaceful man", and the film works so well because of the human connection between Chance and the dying old man. Ben sees himself as the one reasonable man left, and expresses the wish, "I'd like to meet a reasonable man", he's deceived by Chance because he wishes to see himself and his personal ethos affirmed in him. Any worth that Ben had previously found in money and power is sidelined for the moment, as he embraces the fresh air represented by Chance's simply philosophies, "you don't play games with words to protect yourself", Ben tells the displaced gardener. Eve also walks in the garden, (hint) and ironically finds in Chance a lover that affirms her own narcissism. Eve and Ben are so self-absorbed and exist at such a disconnect from most people's reality that they fail to see the fraud that Chance is. Eventually the doctor character (Richard A. Dysart), representing the voice of reason, tracks down the truth about Chance, but as the media juggernaut has embraced him as a semi folk-hero it's too late to stop. Ashby delightfully plays the fantasy out to it's logical conclusion, where a figure who has been anointed as a 'messiah' behaves in a way commensurate with the nomenclature. "Farcical aquatic ceremony" indeed.

The arrogance of the patrician elite is exposed with a subtle but razor sharp wit, and Ashby had a huge critical and commercial hit with the off-beat satire. The miracle that Ashby could work at all within the confines of a studio system, that a film like 'Being There' could be made at all in fact, is a measure of the creative peak the American Renaissance period represented. 'Being There' is as good a marker as any for the end of that era, although 'Raging Bull' makes a good case from the following year, but as America embraced Reagan-ism and corporate greed in the 1980's people like Ashby passed their Hollywood use by date. Ashby was an eccentric, a misfit, and eventually he lived up to Neil Young's maxim, "it's better to burn out, than it is to rust". Thankfully, he left thoughtful masterworks like 'Being There' as his legacy.