Venus disarmed

By Michael Roberts

“There are some things which cannot be learned, though they can be studied. Among them are the laws of art... and the lawlessness of it, as well."

~ Josef Von Sternberg

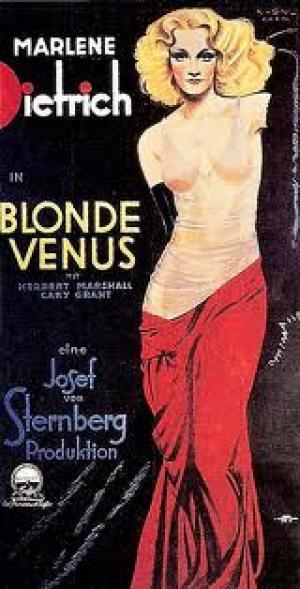

The cinematic oeuvre of Josef Von Sternberg is a highly charged, ultra stylised world of epic internal emotions, generally focused on an obsessive love of one kind or another, and in the case of Blonde Venus it's 'mother love'. To create and fuel that sustained intensity these films mostly maintain a claustrophobic personal atmosphere, rather than invoke a widescreen or epic aesthetic, and in that context Von Sternberg will then fill the frame with his trademark rococo visual flair. As intricate and ornate as the dressing of the sets might be, it's always in service of the story and of the people he's photographing, especially his muse and inspiration, Marlene Dietrich. Von Sternberg and Dietrich continued their incredible run of cinematic collaborations with Blonde Venus, the 5th film in a cycle of seven, and coming after the magnificent Shanghai Express. Von Sternberg used frequent collaborator and Howard Hawks favourite Jules Furthman on the familiar love triangle screenplay, recalling the scenario they worked on with Morocco, and Bert Glennon, who would go on to many John Ford pictures, shot the film in glorious black and white. Herbert Marshall was cast as the husband, and newcomer Cary Grant, who made seven films if this his first year with Paramount, was cast as the suave, younger man.

Blonde Venus starts with a walk in the black forest, as a group of American hikers stumble upon a bevy of German showgirls swimming naked in a lake. Ned (Herbert Marshall) takes a shine to one, Helen (Marlene Dietrich) and convinces her to see him after her show. Von Sternberg presents Helen here as a classical nymph, a siren luring men to an inescapable destiny, a beautiful fantasy creature come to life, and then immediately undercuts the image by jumping forward several years where she's a tame housefrau, bathing her young son Johnny (Dickie Moore) in an unremarkable New York apartment. Ned is gravely ill, poisoned from his work as a chemist and only $1500 will enable him to get back to Germany where a potential cure awaits, but the couple don't have the money. Helen convinces a reluctant Ned to let her return to the stage, and she starts again as a nightclub performer, bringing home enough money for the fare on the first night. "Do you love me"? she asks, after handing over the money, in such a way that it must be apparent she's had to compromise herself severely to get it. Ned leaves, Helen gets involved emotionally with her benefactor, the wealthy and charming Nick (Cary Grant), but resolves to return to Ned when he comes home cured. A timing mix up sees Ned come home early to discover Helen's infidelity, he demands custody of Johnny but Helen absconds with the boy and the pair live life on the run. Ned attempts to have the authorities track down his son, as Helen spirals into a world of poverty and chaos.

The theatre world argot is fantastically well rendered by Furthman, when Helen meets her gold digger co-worker in the club who introduces herself as Taxi-belle, and in a quip worthy of Dorothy Parker, Helen dryly asks "Do you charge for the first mile"? The oily agents and club owners are spot on, and Von Sternberg treats us to three Dietrich musical numbers in the film, the most jaw dropping being Hot Voodoo, Helen's comeback number, a strip tease performed in a gorilla suit! As you do. Helen's return to the stage seems to be the return to her rightful place as the 'goddess' Von Sternberg set her up as at the beginning. Helen has come to believe that a 'normal' life is stifling to someone like her, and that she is doomed to follow her nature and embrace her natural habitat and destiny, even at the cost of her fidelity. Helen is surrounded by opulence when she takes up with Nick, in Ned's absence, but there's no warmth in the environment, and the compromise she made to achieve her ends leaves her empty. Ned returns and she says, "I'm here if you'll have me", hoping he'll recognise what she's sacrificed out of love. When the love of her husband is denied her, she focuses on the intense 'mother love' she feels for Johnny, and fights ferociously to keep it.

The environments Von Sternberg creates for Helen when she's on the run are a tribute to his visual sensibilities, the bar where she looks for work as a prostitute is full of his ornate flourishes."You don't look anything like these other women"?, a potential customer tells her, "give me time", she replies. Von Sternberg shoots his scenes through rainy windows, through curtains, through draped hangings, anything to add visual excitement and interest. Dietrich's face is given the usual careful framing, and either in full frame, or shaded by the brim of her elaborate hats, she never looked more gorgeous. The directors bag of tricks also stretches to the kind of montage Hitchcock would use to get quickly out of one situation to another, greatly contrasted one, where he has Helen go from destitute drunk to major European stage star in thirty seconds flat. The last of the three songs is at the end of the film in Paris, with Helen now a big star, but she's lost her feminine identity completely on the journey between this song and Hot Voodoo, as she dons a man's white suit, and adopts the persona of a playboy who cares nothing about love. This artificial world is the best she can get, a poor facsimile of her life with her family, and an ironic comment on the hollowness of success on those terms. The natural habitat of the 'goddess' turns out to be a fantasy, and an image that gives pleasure to everyone else proves to lie that even she fell for.

The largest gap between Von Sternberg/Dietrich collaborations occurred after this film, and over a year passed before the most visually intense and hyper of the cycle, The Scarlet Empress, was to be made. That film was not the last for the pair, but its immense cost and failure to find a profit put the writing on the wall. Von Sternberg was an obsessive man who channelled his drive into his art, treading on people in the process - it made him an anomaly in the Hollywood studio system and once the store of goodwill he had from making money dissipated, he found it was an unforgiving town for a man who had no friends. Eventually even La Dietrich couldn't save him, as she inevitably went off to make films with other directors. Von Sternberg's cinema du l'amour fou looks more vibrant and interesting and mythic than just about anything the dream factory produced in those years, and it's time his reputation was re-established as an auteur, artist and visionary of the first order.