A Rebel With Meno Pause

By Michael Roberts

'I basically have a very positive philosophy of life, because I don't feel I have anything to lose. Most things are going to turn out okay.'

~ Hal Ashby

Hal Ashby was, like Robert Altman, a generation older than the movie brat, American Renaissance contemporaries of the 1970s that he is often identified with, having worked his way through the editing ranks in the 1960s. Producer/director Norman Jewison was very much a mentor, with Ashby winning the Academy Award for Editing on Jewison's In The Heat of the Night and he then moved into direction, encouraged by Jewison who acted as producer, on his debut The Landlord. Paramount purchased the rights to Colin Harris' screenplay for Harold and Maude, and investigated having the writer direct his own script, but after doing some tests they opted for a more experienced eye, and in Ashby they found someone the quirky subject matter suited perfectly.

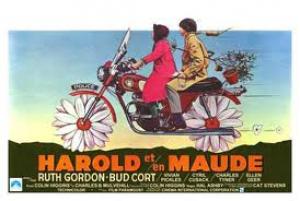

Harold (Bud Cort) is a twenty year old rich kid who has a fascination with death, he is constantly staging elaborate mock suicide attempts and attending the funerals of people he doesn't know. The root cause of Harold's condition seems to be a childhood incident he was privy to seeing where his mother was mistakenly told her only son Harold was burned to death. Harold witnessed his mother display the only real emotion he'd ever seen and has since been attempting to replicate that event, by re-staging his own death over and over. The ruse has now descended to the level of annoying 'sick' behaviour and his mother embarks on a strategy of getting 'computer' dates (in 1971!) for Harold to bring him out of his morbid shell. This is the backdrop against which Harold meets the 79 year old free spirit Maude (Ruth Gordon), a pixie-sprite who forces Harold to reassess his own bleak and unengaged life prism. The two form an unlikely duo as through a series of incongruous vignettes they explore each others attitudes and philosophies, Harold marvelling at Maude's easy and empathetic way with other people, 'they're my species', she replies.

Put simply, Maude has lived a full and rich life and Harold by his own admission says "I haven't lived". Maude's joie de vivre enervates Harold, raising him from his death slumber and helps him discover his connection to life, and in turn repudiates the conservative values his mother forces upon him. 'Normal' society is represented by the Military (Harold's Uncle Victor), Medical (Harold's psychiatrist) and Religious (Harold's priest) who all condemn his association with Maude. Ashby, who wore his anti-establishment credentials proudly, weaves visual allusions to Nixon, Freud and the Pope in scenes involving their counselling against the relationship, making the weight of conservatism impotent in the face of the purity of what Maude offers. This is why the humanity at the heart of the situation trumps any ill-judged prurience that the institutions see in it, elevating the liaison to a deep and mystical attachment. Maude has triumphed by sheer force of will, her struggles only hinted at, her concentration camp tattoo making Harold's death fixation look positively dilettantish, she is a force of nature and is his entry point to a nature he barely knew existed. When Harold admits he is in love with Maude on her 80th birthday she gently touches his face and says, "What a perfect farewell, go and love some more".

Ashby also plays with the gender/generational and class divide, subverting expectations at every turn. Maude is a bigger rebel in every way, much more than many of the counterculture icons, and she's from a generation that the hippies had rejected wholeheartedly, a reminder that human spirit is not limited to age and gender. Maude was a nature loving peacenik when the hippies were not even a gleam in their daddies eyes. Ashby used the meditative folk ambiance of songs by singer-songwriter Cat Stevens while he was editing the piece as temporary mood appropriate music but became so attached to the sound with the visuals he approached Cat Stevens to contribute to the soundtrack. Stevens agreed but only had time to do two demo songs as his career was skyrocketing, Don't Be Shy and If You Want To Sing Out, and was mildly pissed off when Ashby used the demos in the finished film before he had a chance to record them properly. That's showbiz. Regardless the use of his music is intrinsic in establishing the emotional tone and centre of the film. and the use of the song Trouble at the end is one of the most seamless and beautiful integrations of a 'pop' song in all of cinema.

Harold and Maude came at a point in the counterculture cycle where the hippie dreams of a peaceful new world, the 'daisy in the barrel of a gun' Woodstock hope, had all but dissipated in a welter of violence from 'the Man'. Altamont, Kent State University, Richard Nixon's presidency and the ongoing and unpopular Vietnam war all added up to an America as far from the hippie idyll as it ever was, and Ashby obliquely threads these concerns into the context of the film. Ashby is looking at a society suffering an existential crisis, he distils it through the focus of one young man's struggle and reminds us that meaning is found internally, not imposed externally. The extrovert Maude challenges and teases out of the introvert Harold a life that can be lived on one's own terms, even if those terms are counter to what the 'norm' offers. Harold starts the film as a white sheet of a boy, and Ashby gradually infuses colour into his cheeks as he comes to life, a nice visual trope with which to underline his point.

Bud Cort, who did well in Altman's Brewster McCloud the previous year, will forever remain Harold in the eyes of the public, so identified with that quirky character it seemed Hollywood was unable to think of a further use for him. Ruth Gordon became a star with her turn in Polanski's Rosemary's Baby in 1968 and solidified her place in the firmament with this iconic role, and unlike Maude she lived to be 99, without her brilliant and bold performance the film could work as well as it does. Harold and Maude flopped at the box office, Paramount had the balls to make it but not the wit to promote it suitably, even they baulked at a scene Ashby proposed of full on foreplay between the couple as they make love, which would no doubt have added to the unease and trepidation. Since then it's been recognised for the clever and endearing film that it is, and if ever one movie defined the term 'cult classic' this is surely it, and its survival and reputation owes something to Ashby's later successes, as he proved to be very in touch with the '70's zeitgeist in America and made several enduring classics. None more so than this off-beat charmer.