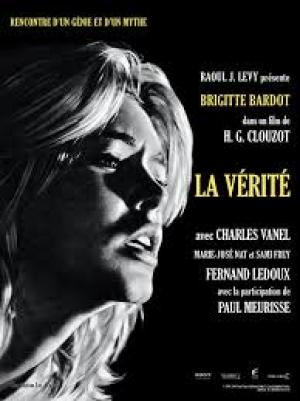

Clouzot et Bardot

By Michael Roberts

Henri-Georges Clouzot made La Vérité in 1960 and effectively threw youth culture back in the fresh faces of the Nouvelle Vague filmmakers who had condemned him as irrelevant and part of the maligned Cinéma du papa, the progenitors of the despised ‘tradition of quality’ of elitist and moribund French cinema. Clouzot’s exacting personal cinema was in no way reliant on ‘stars’ but producer Raoul Lévy gave him the opportunity to work with the biggest star of French cinema, Brigette Bardot and Clouzot couldn’t resist. He embraced the clout and pizzazz that came with her, obviously deciding that he could affirm his relevance in the face of the Nouvelle Vague and re-start his career in the brave new world of the 1960’s.

Dominique (Brigette Bardot) is the gorgeous but restless daughter of respectable provincial parents, living in the shadow of her ‘goody two shoes’ sister Annie (Marie-José Nat). Annie has the talent and discipline to become a serious musician and wins a scholarship in Paris, but Dominique takes the opportunity to tag along and leave her small town roots for good. The sisters are chalk and cheese, Annie studious and shy, Dominique extrovert and narcissistic, and trouble intensifies when Dominique takes an interest in Annie’s crush and fellow musician, Gilbert (Sami Frey). Dominique and Gilbert embark on an affair that takes them in different and surprising directions with tragic consequences. Dominique is put on trial for Gilbert’s death and two fierce legal minds argue the case in the sensational trial, Guérin (Charles Vanel) for the defence and Éparvier (Paul Meurisse) for the prosecution.

In many ways Clouzot is essaying in microcosm the generation gap that would blossom world wide, within a few short years, into the Baby Boom led counterculture. Dominique falls into the Rive Gauche world of bohemia and promiscuous behaviour, attracted to the nihilism and rebellion she finds in the arts community and promptly goes through her own existential crisis, “wanting to die is serious” she says. Dominique wants to find something to live for and thinks she has in Gilbert, but the narrative hangs on who exactly betrays who and why? The lawyers make a case for both Dominique and Gilbert as the wounded parties but Dominique’s attractiveness blinds the mostly male law officers into stereotypical and sexist assumptions. “She’s a looker”, we hear as Dominique enters the court, also that “men pursued her like game”, before she’s then branded “lying, immoral, shameless”.

Ironically, Annie and Gilbert represent the establishment, their conservative lifestyle and conventional philosophy reflected in their musical taste, the opposite of the carnal dance music that Dominique favours. Clouzot is effectively showing that the battle is not only between generations, but between philosophical positions within the same generation. Annie spits at Dominique during the trial, “he was marrying me!”, only to hear “to darn his socks” from her sister. Gilbert is a man in a comfortable rut, conforming to his parents and to society’s expectations of his privileged lot, when Dominique shows him the possibility of another life, vivid and engaging.

The key question turns on how much Gilbert was using Dominique for his own ends and if he even loved her at all? Clouzot established the ground for a close examination of Dominique’s morals in a patriarchal society and it is through this prism that the ‘truth’ emerges. Dominique’s freedom and liberalism threatens the hidebound status quo, and her crie de couer to the judges from the dock, “you’re all dead” rings out as a challenge to their lifeless philosophy. The listless young generation that Dominique falls in with represents an existential crisis en masse, as Clouzot deals with a post war France struggling to find meaning in a cold war world, indeed it seems a generation is on trial as much as Dominique.

Clouzot set an austere tone from the outset; a delicate piano sonata presages a serious and sombre dissection of love and betrayal. Clouzot was the master of elegant visual motifs and exquisite mise en scène, as exemplified by his lovely early shot of the ‘broken’ Dominique gazing into a fractured mirror. He moves seamlessly from perfectly orchestrated court room sequences to vibrant or moody flashbacks with deceptive ease, incrementally building the picture of a maligned and misunderstood woman. Clouzot’s command of every aspect of the filmmaker’s craft imbues every frame, pace and tone and performance are all top shelf, as is the fine and intricate script which includes contributions from himself and his actress wife Véra, who sadly died shortly after filming concluded.

The unexpected teaming of France’s hottest star, known for her frivolous and sexy romps with a veteran director regarded as a martinet perfectionist should, in all probability, not have worked at all. The relationship was fractious and Bardot complained that Clouzot was a tyrant, even though she came to regard this as her best performance, and rightly so. By the time Clouzot worked with her Bardot had been through the fame wringer and her history of breakdown’s and rumoured suicide attempts saw Clouzot push her to the edge in order to extract a performance that rang true. Clouzot allegedly gave her tranquilisers or booze to push her along, grabbing her and screaming, “I want an actress, not an amateur!” Bardot supposedly replied that she wanted “a director, not a psychopath.” Touché. She survived and went on to work with some fine Nouvelle Vague figures in Jean-Luc Godard and Louis Malle, making the excellent Contempt and Vie Privée respectively for them and proved again to be a fine actress in the right part.

The ultimate irony for Clouzot was to watch the terriers of the Nouvelle Vague champion Hitchcock while they poured scorn on his imposing body of work. He may have been used to being misunderstood, his resistance masterpiece Le Corbeau was bizarrely thought to be sympathetic to the Germans, resulting in Clouzot being wrongly accused of collaboration after the war and of spending time in jail before the decision was overturned on the back of outrage within the arts community. Clouzot had seen it all before and seemed to prefer to let his work, which he pursued with an obsessive passion, to stand for itself

Bardot went on to an undistinguished career as an actress but a sensational one as a sex symbol and movie star, while Clouzot attempted to gather the energy for the exhausting project that nearly killed him, the remarkable (and unfinished) L’Enfer. It would be an irony to end all ironies that one of the fathers of the movement that dismissed him, the Nouvelle Vague, Claude Chabrol (and the man who wrested the mantle of the ‘French Hitchcock’ from Clouzot) was handed Clouzot’s script for L’Enfer by his estate and finally made the film in 1994. Henri-George Clouzot’s reputation is now that of a master of cinema and far outstrips that of most of the New Wave brats, and a film like La Vérité only underscores that richly deserved assessment.