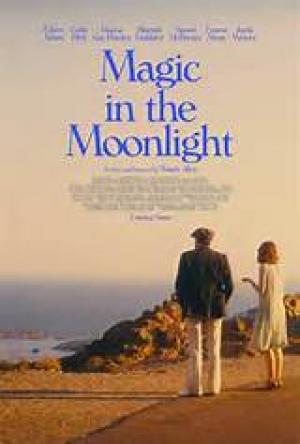

Woody's get existential in France

By Michael Roberts

"I am not afraid of death, I just don't want to be there when it happens."

~ Woody Allen

Woody Allen continues his remarkable late career flourish with his witty treatise on the afterlife, Magic in the Moonlight. Allen has long been obsessed with loss and death, and here he reaches a kind of apotheosis as he outlines the pros and cons of the life after death debate via his stand-in sceptic, played by Colin Firth, a magician who attempts to trip up a young spiritualist, played by Emma Stone. After spending most of his career delineating his own personal neuroses and defining the modern idea of Manhattan for the rest of the world, Allen has spent much of his recent time setting his philosophical ruminations in the ‘old’ world of Europe, and here he sets his fable in the glorious surrounds of the South of France, crucially, 10 years after the end of WWI.

Stanley Crawford (Colin Firth) is one of the most successful magicians in the world, a demanding perfectionist who presents his stage character in the form of mysterious oriental, Wei Ling Soo. Howard (Simon McBurney), an old school friend and rival appears with a proposition, he needs help in debunking Sophie (Emma Stone), an American psychic medium that is in the process of fleecing some of his rich friends by pretending to contact the dead scion of the family to impress and inveigle the surviving matriarch (Jacki Weaver) into financially supporting her schemes. Stanley is confident he’ll be able to spot the usual tricks a medium employs, but is staggered to find he may be dealing with somebody who can actually communicate with the dead forcing him to re-evaluate everything he’d held as fact.

History has a habit of throwing up periods of reassessment after periods of great calamity, and the era directly after WWI was no exception. Allen begins his word-fest on the theatrical stage in Berlin, 1928, in the brief window of escape that saw the artistic explosion of the WeimarRepublic, prior to the rise of fascism and Hitler’s ascent to power in 1933. America, after the disastrous Civil War of the 1860’s experienced a similar phenomenon of embracing the supernatural, outlined beautifully in Brenda Wineapple’s seminal book, Ecstatic Nation, where massive national loss and grief was exploited by ‘mediums’ suddenly adept at contacting dead soldiers and communicating messages of love and support, usually in sold out town hall appearances. The 1920’s were ripe with philosophical debate, a time where the French particularly set the foundations for the emergence of Satre and Camus and the idea of Existentialism.

Woody works his faux- Nietzschean philosophising in the world of the super rich, just before the market crash and onset of The Great Depression, a time where the greatest disparity of wealth existed in the USA, a statistic that aptly enough was replicated in 2014, the year of the film’s release. Stanley is a man who luxuriates in his own certainties, a man convinced of the value of (emotionless) logic and reason in the face of supernatural wishful thinking. Emma tells Stanley, "unlike you we're members of the working class" and represents emotion, an area that the supernatural snake oil sellers exploit when the conditions are ripe, i.e. when people are emotionally vulnerable and therefore prone to irrationality. When Stanley becomes emotionally vulnerable he flirts with abandoning his long and deeply held beliefs, unable to face the harsh reality of losing someone close to him. Emma complicates his life as she also represents a joy for living that his logical cynicism has forbade him, as he has sublimated his inner child to a need to seek perfection and safety, rather than embrace an emotional life of flaw and risk. The misanthropic Stanley, "a perfect depressive with everything sublimated into his art," has created the illusion of a perfect life, but Emma's vivacity forces him to realise how empty it is, just as much a chimera as his own magic act.

Stanley experiences his own existential crisis in his dealings with Emma, and confronts the proposal that there is comfort in the supernatural, in the things that his logic can not explain. Allen is pursuing a line that asks the question, “if a lie is beneficial and provides solace, is it worth embracing, and what do we lose in the process?” Stanley provides the answer, we lose our dignity and self respect, and that’s a price he’s unable to pay. Stanley finds a way to lose his cynicism, to embrace the inherent imperfections in life and to find a deeper meaning in a life of logic and reason in a natural universe, where the ‘unknowns’ are merely waiting on a natural explanation, rather than a fanciful and speculative supernatural one contemptuous of the rules of evidence, in other words an existentialist solution.

Colin Firth again proves himself one of the most accomplished actors of his generation, achieving an effortless authenticity with his deft performance, and Emma Stone delivers nicely as the lively young American. Allen fleshes out the cast with never less than convincing character actors, with Hamish Linklater very good as the chinless rich boy Brice and Eileen Atkins a standout as Aunt Vanessa. The fine Australian actress Jacki Weaver continues a run of excellent support slots in the role of the aging widow, and McBurney is a delight as the duplicitous Howard. The soundtrack choices are, once again, superbly realised by a director who is also a fine musician and Jazz era aficionado to reckon with.

Woody Allen, for all his renowned pessimism, has managed to affirm the value of love above all in this two handed debating class, and if the format is flawed because of the relentless back and forth of those supposedly ‘dry’ ideas, it still has interest and appeal. The older Woody is confronting his own mortality in a way that the younger Woody could never have done, and his hard won wisdom shines in a script that has nuance and depth, but not much fun as such. Woody knows that the natural universe can supply transcendent experiences to anyone open to the sublime, an area not exclusively the domain of the religious or superstitious, as he acknowledges the ‘magical’ and mystical quality of love and of the natural universe by setting part of the film in an observatory. These are serious issues, and while Woody frames them in an entertaining way, via the theatricality and decadence of the time, the gravity of the intellectual discourse still compels and intrigues even if the dialogue sometimes fails to sizzle.

Magic in the Moonlight may be a cinematic sleight of hand and not first rate Woody, but second rate Woody still outshines most of what passes for excellence these days, and it is still the work of a master filmmaker with something to say in the third act of his career, a miracle of sorts and magical in itself.