A trio in Rio

By Michael Roberts

"Who better than an Irishman can understand the Indians, while still being stirred by tales of the US cavalry"? ~ John Ford

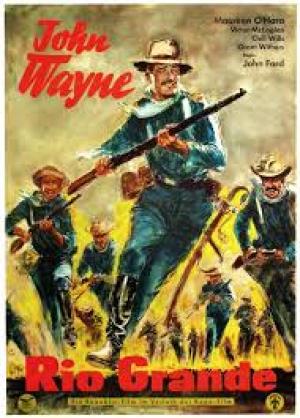

The Cold War was heating up in 1950 and about to find a line in the sand at the 38th parallel in Korea, as John Ford was putting the pieces in place to create his dream project, The Quiet Man. As part of a deal to get that Irish themed film made, Ford struck a conditional contract with Herbert Yates at Republic to firstly provide a western hit that would indicate Ford’s ongoing commercial viability, and so Ford turned to a nasty piece of work that he initially christened Rio Bravo. Ford turned to his go to collaborator, John Wayne, teaming him up with the beautiful Irish colleen, Maureen O’Hara, his luminous star from How Green Was My Valley, the same stars he would again cast in his dream feature in 1952. There is a school of thought (and some indications) that Ford was going through the motions in churning this work out as a routine programmer, but the innate artistry he possessed and the precision honed abilities of his battle hardened stock company produced something miraculous in any case.

Lt Colonel Kirby Yorke (John Wayne) is a veteran of the Civil War and commanding a remote outpost near the Mexican border. Yorke is no martinet, he’s a competent, level headed and much admired leader who gets a surprise when Jeff Yorke (Claude Jarman Jr), the son he hasn’t seen for 15 years, arrives in the latest intake of raw recruits. Jeff’s mother Kathleen (Maureen O’Hara), and Yorke’s estranged wife soon arrives with the intention of buying her son out of the service, but neither father nor son will sign the necessary forms to realise her scheme. An uneasy relationship between the three plays out with the powder-keg pressure of marauding Apache’s making frontier life a hazardous and fraught existence.

John Ford had recently made two cavalry pictures, Fort Apache in 1947 and She Wore a Yellow Ribbon in 1948, both based on short stories by Saturday Evening Post writer James Warner Bellah and the fact that he wanted to quickly complete another film based on Bellah’s Mission With No Record seems to indicate an off-hand attitude to the project. Rio Grande made for a neat ‘cavalry trilogy’, but that was never Ford’s intention, its worth fitting more in line with the taciturn director’s “just a job of work” ethos, his dismissive way of downscaling his artistic or poetic dimension. In Ford's world artists were sissy's, and heaven help anyone who thought John Ford a sissy.

Rio Grande also needs to be seen in the light of Ford’s increasing conservatism, indicated by his choice of screenwriter for the project, the right wing James Kevin McGuiness, instead of his liberal leaning regular collaborator Frank Nugent. Nugent was noted for writing sympathetic portrayals of Native Americans, but the Indians in Rio Grande are a one dimensional and villainous lot, closer to caricature Nazi’s than a much put upon indigenous people battling imperial genocide. General Sheridan’s (J. Carroll Naish) verbal and illegal order “I want you to cross the Rio Grande, hit the Apache and burn him out! I’m tired of hit and run, I’m sick of diplomatic hide and seek,” could be the cry of the Allies fighting a ‘clean’ war against those nasty Nazi’s who were not playing cricket!

Ford spent the war years serving in the Pacific, shooting actual battle footage at Midway for a Naval Field Unit, was present in France for D-Day and rose to the rank of Commander. His post war films leaned heavily towards showing the military in a positive and mostly romantic light, albeit with the occasional dose of grittiness a la They Were Expendable, but the further away from the war it seems the softer his lens of all things military became. Ford was a supporter and acquaintance of General Douglas MacArthur, a racist with a streak of fascism who ran foul of President Truman to the extent he was sacked for insubordination, and Ford himself was not above belittling his friend John Wayne for his lack of military service. The western and/or military film made up almost all of Ford’s post WW11 output, where the western’s tended to take on darker themes as against the sentiment and hagiography of the military films. Hollywood quickly mythologised the WW11 heroes, and went light on any nastiness (thank you for your service) so it was easier to admit to a darker or ugly underneath if the setting was a couple of generations removed.

Immediately prior to Rio Grande Ford filmed his under-stated masterpiece Wagon Master with veteran cinematographer Bert Glennon, and he again turned to the brilliant technician to frame the dusty expanses of the Mojave Valley in Utah. The film contrasts the vast and desolate terrain with the small, isolated white community at odds with the indigenous population, fighting for their land and retreating across the border for safety when required. Ford gives free reign to expressing his usual regard of community and also to the absolute primacy he placed on the doing of duty, and Yorke’s dilemma is a typical Ford-ian one, reconciling his personal life with his public duty. In Maureen O’Hara and John Wayne he found an ideal pairing for his traditional views of male-female relationships, and would try to team them up another 3 times in the next decade, succeeding in The Quiet Man and The Wings Of Eagles, but missing out on The Long Gray Line where he had to settle for Tyrone Power instead.

Rio Grande is a deceptively adept western, made in the same year as Henry King’s The Gunfighter and Anthony Mann’s Winchester ’73, it shares the same bleak heart as those fine films, showing that not only Film Noir crime pictures were affected by the bloody legacy of WW11. Ford leavened the darkness of the genocidal actions of the soldiers with the re-kindling of the personal love between Yorke and Kathleen. He also employed his trademark use of music from Sons Of The Pioneers, and of ritual in the framing of a dinner and dance to ease the tension of frontier life. Ford had rarely made what he considered to be a “mature love story”, but with Rio Grande he certainly set the scene for what was to come with The Quiet Man. John Wayne showed just how much he’d benefitted as an actor from working with Howard Hawks on Red River, and delivered a fine, nuanced performance, matched every inch of the way by the luminous O’Hara.

John Ford was never one to rate his own films (the contrarian in him rated The Fugitive as his best work) but Rio Grande is a real gem and showed what a well-oiled machine can do when all the elements of Ford’s stock company were put to work. In a sad postscript, the old bastard would fall out badly with Maureen O’Hara, the two trading insults for years, oddly she was convinced it was because she accidentally saw him kissing a male on a set and thought him to be a closet homosexual. She also proffered that Ford was in love with her, and after seeing the work she offered him in Rio Grande and the others, you could hardly blame him.