Travis shoots, Herrmann scores, Marty cleans up.

By Michael Roberts

'My whole life has been movies and religion. That's it. Nothing else.' ~ Martin Scorsese

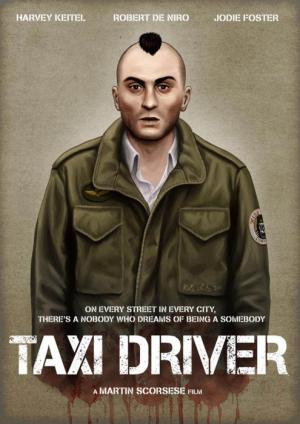

Martin Scorsese and Paul Schrader’s seminal neo psych-noir, conjured from the mean streets of New York, provided American cinema with a nightmarish, hallucinogenic jolt to the system, ably partnered by Robert De Niro’s startling and brave performance in the title role. In Travis Bickle they presented a superficial anti-hero, a ‘nobody’ so alone and disconnected, indeed the posters for the film’s promotion spruiked ‘a nobody who wants to be a somebody’, but a closer look revealed a sociopath, isolated, disturbed and irredeemable. Scorsese’s film speaks directly to the times, coming from the turmoil of Vietnam and the scars that the Asian war left on the American psyche, it suggests a society unsure of it’s values and in Bickle it finds an avatar to represent paranoia and self-loathing for all. Scorsese constructed a dark New York of the id, as phony in it’s own way as the Hollywood ‘dream’ New York confections of his youth that were all designed on Californian sound stages, lit as a rain soaked, neon urban jungle, it’s no surprise to find an ex-marine emerge in full battle kit as a warrior for these dank times.

Scorsese opens the intensely visual film with an iconic blast of New York street steam, and from it emerges a stallion without a knight, a sleek New York yellow cab, prowling the darkness like a stalking animal. A troubled knight appears in the form of Travis Bickle (Robert De Niro) an ex-vet who’s having difficulty sleeping, he gets a job as a driver who is prepared to go into any neighbourhood, this sets him apart already from many of his colleagues. Travis soon becomes fixated with pretty political volunteer worker Betsy (Cybill Shepherd) and persuades her to meet for coffee, where his awkwardness is almost endearing and intriguing. The date she agrees to sets the tone for her to see Travis is not quite right, as he takes her to a hardcore porn film for a movie night. At this point Travis abandons his aspirations and attempts to integrate and conform to a ‘respectable’ society, and begins to focus on the people at the lower social levels of the city, the junkies, criminals, pimps and dealers that he sees every night. Travis is motivated by the plight of Iris (Jodie Foster), a 12 year old prostitute run by Sport (Harvey Keitel) and he sets about to ‘free’ her from her life on the streets.

Schrader’s Calvinist upbringing, combined with Scorsese’s Catholic perspective sees Travis adopt the trappings of a zealot, or of an adept, as he trains his body ferociously and also his mind to be the ‘real rain’ he longs for, one that will clean the scum and the filth from the streets for good. He attempts to pull himself back from the brink by reaching out to his taxi driver colleague Wizard (Peter Boyle), but Travis is beyond reach by this point, and soon the only one talking to Travis is Travis. He arms himself with a small arsenal and sets his sights on Betsy’s political ideal, presidential candidate Senator Paladine, not for any ideological reasons, but more out of revenge towards Betsy. Travis proves inept as an assassin but moves his attentions to Sport and Iris and moves inexorably towards a bloody climax.

Scorsese slyly presents Travis’ change visually with his changing haircut. Travis starts out with a reasonably shaggy head of hair, but as he descends to a starker and more ascetic like, the hair gets shorter, until it’s virtually ‘to the bone’, the stripped down, urban jungle warrior, the real deal ready to take on his holy quest. Travis in attempting to eliminate Paladine is trying to destroy a society that he feels America pushes him to aspire to but has no access to, a condition that many Vets felt upon returning home to a society that unfortunately damned them for the unpopular war that the politicians had foisted upon the country. Travis, ever the outsider, also cannot fit into the lower depths that are his natural habitat, and rather than embrace these equally ill-fitting fellow travelers he despises them for the weakness he sees mirrored (literally) in himself. ‘You talkin’ to me’? In attempting to destroy Sport he is committing a kind of suicide, and Schrader underlines this by a failed suicide attempt at the end of the carnage.

Travis is perpetually outside looking in, eloquently framed by Scorsese by showing him staring at a TV, holding his gun watching young couples romantically dancing together as Jackson Browne’s plaintive middle class angst-pop plays Late For The Sky, this is a poetic world so completely alien to Travis he may as well be singing in Latin. Elsewhere in the film it's legendary composer Bernard Herrmann’s angular score that keeps the audience’s teeth on edge, alternately jarring or lulled into a deceptive sense of calm via the languid saxophone notes. Hermann, a soundtrack immortal for his work with Hitchcock, was drawn to Hollywood by his New York radio collaborator Orson Welles to score Citizen Kane, an auspicious enough beginning, and he died shortly after completing Taxi Driver, which Scorsese dedicated to his memory.

Scorsese’s use of extreme and brutal violence works because it is contextual, the build up to the pay off makes it believable, and therefore all the more shocking. Scorsese understands that violence should repel and shock us, and it’s only by contextualisation can this occur. It may be a lesson he needs to relearn, amongst many of his fellow modern directors. The denouement attracted a lot of mixed analysis and still does. Schrader insists Travis ’isn’t cured’, and in keeping with the sociopath cycle he would be destined to suffer a build up of frustration and emotion until a release came to calm him down again. This suggests that even if the Betsy ride at the end looks like a dream, and it swirls and dances across the screen in a way that makes it pure visual poetry, it was a surreal footnote to Travis’ sudden notoriety. If even Betsy, who should know better, is somewhat in awe of Travis’ ‘achievements’, if even her instincts have been compromised and her judgment called into question by the media circus surrounding his actions, then what hope for the rest of us to deal with the many Travis Bickle’s that walk the dark streets.

Robert De Niro’s commitment to the role was typical of his dedication and drive, it perfectly compliments both his earlier muscular work for Scorsese and his higher profile work in The Godfather II and the dead-eyed Bickle would be one of his signature characters in a crowded gallery of brilliant ’70s performances. De Niro’s ability to walk a line from awkward misfit to rampaging avenging angel is truly astonishing and marked him as the great alpha male inheritor of Brando’s crown. The supporting roles are all alive with flair and spark, all ringing true in a robust and authentic way. Scorsese even throws in a cameo from himself, hectoring Bickle form the back of the cab. The cinematography from Michael Chapman is nothing less than amazing, from surreal and nightmarish, to docudrama gritty, superb. Taxi Driver catapulted Scorsese into the first rank of cinema’s giants, and he remained there for decades, his remarkable and prescient paean to alienation as salient as any engraved on celluloid. A film for the ages.