Roman-esque

By Michael J. Roberts

"I would like to be judged for my work, and not for my life."

~ Roman Polanski

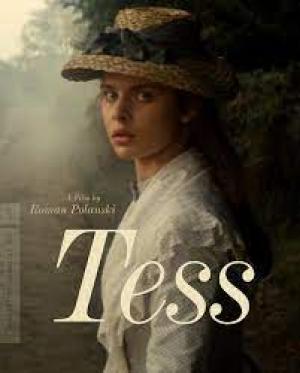

Roman Polanski’s late wife, Sharon Tate, had given him a copy of Thomas Hardy’s 19th century novel Tess of The D’Urbervilles with the aim of him directing a film version for her to star in. Tragedy intervened in the brutal shape of Charles Manson and his twisted Family, and that film was never made, but after Polanski has reached a self-assessed career nadir with The Tenant, he returned to the property as the chance for redemption and a change of pace. French screen legend Claude Berri produced the film and that most English of literary properties would be entirely filmed in France, directed by a Polish man and with a German actress in the lead (C’est showbiz, n’est pas?!) But what an actress Polanski found in the luminous Nastassja Kinski; a girl surely born for the silver screen being the daughter of the iconic German actor Klaus Kinski.

Tess (Nastassja Kinski) is the beautiful young daughter of a poor Wessex farmer who discovers he is related to an old, noble bloodline, the d’Urbevilles. He becomes convinced that he is entitled to a slice of the blueblood pie and sends Tess to meet Alec d’Urbeville on a grand estate some distance away and plead the family’s case. Alec (Leigh Lawson) is a ne’er do well scoundrel of the old school and it transpires that the noble name he bears was only purchased by his wealthy and dotty mother to add a sheen of respectability to their ‘new’ money. Alec at once sets his sights on his notional cousin’s virtue and when she proves resistant, he forces himself upon her. She returns to her family and eventually finds a pure love with the idealistic preacher’s son, Angel Clare (Peter Firth). The happy couple marry but the unhappy past with Alec unexpectedly catches up with her.

Polanski, emotionally and mentally, was damaged goods after the brutal and sensational murder of his wife and he struggled for some time to come to terms with both his own demons – the residue of a boyhood in the Warsaw ghetto during WWII and the more recent Manson induced ones. Polanski made devastatingly poor personal choices that crossed into criminal behaviour in L.A. and began his life as persona non grata in the wider world after he fled the States because of the scandal involving the underage Samantha Geimer. Polanski started work on Tess as a French resident and in retrospect his choice of focusing on the life of a young desirable woman seems a loaded one, but the world at the time seemed to ignore the connection, one that in the 2020s seems blindingly obvious, even given the project pre-dated his crime and was suggested by his dead wife.

The artist therefore may be problematic, but what of the art? Tess is mesmerizing on so many levels. It’s a considered work on the nature of fate and of class and opportunity and it’s a morality tale for the ages. Polanski reveals his hand slowly, every frame and set up considered and rendered with a painter’s eye. The gorgeous French countryside makes a convincing Wessex stand in and the exterior photography from Geoffrey Unsworth is superb, but Unsworth’s untimely death during filming meant that Ghislain Cloquet

(a Robert Bresson favourite) completed the cinematographic duties and duly shared an Oscar for their efforts. The score is a memorable one from Phillipe Sarde, and the screenplay adaptation was done by Polanski in concert with his regular collaborator Gerard Brach.

Tess works brilliantly because Polanksi is in complete control of the myriad elements at his disposal and because Kinski is perfect in the title role. Both Polanski and Claude Berri knew the project would stand or fall on the casting of the central character as she carries the film and is rarely not at the centre of the action, so they persevered, encouraged and nurtured her as an actress. She delivers a beautifully realised characterisation and creates a figure for the ages in the definitive screen Tess. Polanski surrounded the young actress with fine support from Leigh Lawson and Peter Firth who represent two different kinds of masculinity. Hardy was working in the folk tradition of tales of love and betrayal, of lust and violence that have been part of the storytelling tradition for centuries. Hardy may have been constrained by the Victorian era pruderies and censoriousness in all things sexual, but not so Polanski. The central struggle and the sexual nature at the heart of the piece is given full and compelling scope in all its contrasting brutality and tenderness.

Tess is dirt poor and has no prospects, and being a woman in the late 1800s she also has little agency in her own future. Her father would undoubtedly have known that to send her on the initial errand was tantamount to pimping her out, but he repressed any notion of protecting her in favour of the chance of a payout. Tess does learn the cold facts of life for a woman of her time, made doubly difficult by the fact that she is a true and devastating beauty able to entrance a reprobate like Alec. She also learns that she will be forever on the wrong end of a double standard, where women with a sexual past, even one where they were victims of abuse, will be judged differently from a man whose sexual past will be taken for granted to be no impediment for his future. It is a world where sexual language is spoken in code, whispered and hinted at and yet Polanski is able to set these exchanges in superbly realised set pieces of subtly loaded glances and physical innuendo.

Polanski contrasts the bleakness of the personal situations and the squalor and drudgery of the working class against a backdrop of sublime landscape and natural beauty. For a woman like Tess, or any in her position, love or the idea of love at least holds the only hope of joy or promise (however illusory) that she might aspire to in order to the relieve the grinding reality of her station, and Polanski keeps that tragedy in full focus. Class and wealth are at the centre of a patriarchal system that grinds innocent creatures like Tess as surely as the thrashing machines she works with in the fields grinds the wheat.

Tess is a masterwork of framing and glorious composition, but always in service to the story so that we are never in doubt about the desires and intentions of the protagonists, in all their messy complexities. The work is a classic of its kind and a fine adaptation of a canonical English literature treasure. The very flawed and very human Roman Polanski made a masterpiece for the ages, and regardless of his persona non grata status in the cancel culture era, his screen output stands apart and tribute to his ability to illuminate tragedy and uncover the darkness and the light in the human experience. Something he was all too well acquainted with.