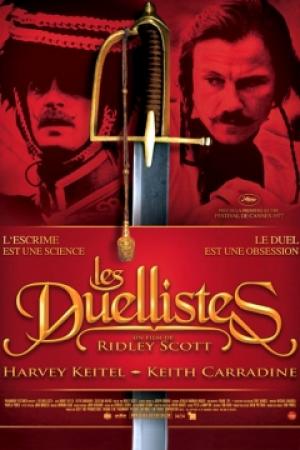

Ridley pre-Ripley

By Michael Roberts

"The Duellists won Cannes, but Paramount didn't know how to release a film about two guys in bizarre breeches, waving swords around. I actually think it's a pretty good Western." - Ridley Scott

Like those of Truffaut, Malle, Godard, Huston and Welles, Ridley Scott is in a very small anthropological class of brilliant feature film debuts and his The Duellists is a ravishingly shot period piece that also won the prize at Cannes in 1977 for Best Debut feature. The scenario is based on a true one and is taken from a Joseph Conrad short story fleshed out by screenwriter Gerald Vaughan-Hughes, condensing the actual series of 30 odd duels across 19 years to 5 duels across 15 years. Scott was working on a small budget and had cast Oliver Reed and Michael York, but Paramount would only let him use American stars from a short list of 4, and from that Scott selected the two most appropriate, but in saying that both Keith Carradine and Harvey Kietel were cast against type to say the least in playing Napoleonic era cavalry officers. Scott had attempted to get up a period piece about Guy Fawkes called Gunpowder Plot, but when he found this story for free, as it was out of copyright he pitched this and got the green light, Kubrick’s Barry Lyndon fresh in everyone’s memory, including Scott’s.

The voice over from narrator Stacey Keach likens honour to a kind of hunger, as we see a beautiful shot of a young girl herding her geese along a bucolic country lane, her rural peace is then abruptly disturbed by a duel being fought in a nearby field, and we see Hussar cavalry officer Feraud (Harvey Kietel) run through his opponent with a blade. Feraud has unfortunately injured the local mayor’s son and his commanding officers send d’Hubert (Keith Carradine) to arrest him. Feraud takes the timing and place of the arrest as an insult, and regards d’Hubert as a mere ‘office lackey’ and not as an equal brother officer and so challenges him to a duel. d’Hubert gets the better of Feraud and in doing so brings disrepute on his own head in the regiment, telling the surgeon (Tom Conti) that he demanded an inquiry, but war intervenes and no investigation into the incident is held. The surgeon speculates that the pair are carrying a feud through the ages as re-incarnations of previous lives, and are becoming objects of some fame. After 6 months of war the pair meet again, Feraud demands a re-match and this time d’Hubert is injured and unable to continue, but Feraud will not forgive and his honour remains unsatisfied. d’Hubert’s girl Laura (Diana Quick) is appalled by the continuing fighting and after a fortune teller’s tarot card indicates she’s caught between two mad dogs she decides to leave, writing ‘goodbye’ in red rouge on the blade of d’Hubert’s sword.

d’Hubert practices his swordplay, realising that Feraud is an ‘enemy of reason’ and that another contest is inevitable. The third duel is caught mid flight, in a large bricked bunker with both protagonists bloodied and exhausted, after they fight each other to a standstill their seconds pry them apart and take them away. d’Hubert is promoted to Captain and ordered not to fight and after a period of 5 years they meet again with Feraud also a Captain and challenging to a duel on horseback. The pair are famous now, like renowned ‘fire-eater’s’ and people are running books on who will win as they front at dawn in their best Hussar finery to charge across the field at each other. Feraud is like a caged lion, fearless and driven, whereas d’Hubert is going through the action as a point of honour, terrified by the potential consequences, to the extent that during the charge he has his life flash before his eyes. Feraud is wounded and another period of 6 years passes where the pair are caught in the ‘armageddon’ of Napoleon’s disastrous Russian campaign of 1812, this time weary and ragged they actually face a common enemy in the Cossacks and put aside their personal feud for a moment, but agree that the next time it will be with pistols. d’Hubert pauses in the snow and the blood to gaze upon a frozen soldier, who appears to be a ghost of himself, mocking what’s become of the once proud officer, reduced to a husk in a distant foreign hell.

Two years on and d’Hubert has recovered at his sister’s estate in Tours where he is introduced to a suitable bride in Adele (Christina Raines). he likens their eventual marriage to a social contract, an arrangement not unlike a duel that satisfies convention and has winners and losers, it’s telling that he cuts the wedding cake with the blade of his sword. It’s plain in his mind he’s fulfilling his role as a duellist like a reluctant bride in order to satisfy the convention of honour, the disgrace of not doing so being even more impossible than the act. He’s called upon by a colleague (Edward Fox) of Feraud’s to support Napoleon’s ill-fated return from exile on Elba, as Feruad is doing, but declines. After Napoleon’s defeat Feraud is imprisoned and is to be executed for his part in supporting the Emperor but d’Hubert secretly intervenes with the Minister of Police (Albert Finney) and Feraud is released. Feraud tracks down d’Hubert for the final showdown with pistols, and in a ruined castle, a metaphor for the ruination that Feraud has become, he stalks d’Hubert. Feraud ends up at the end of d’Hubert’s remaining loaded gun begging to be killed, only to be told that the feud is over as according to convention his life is now owed to d’Hubert, who declares him to be a dead man and expects him to behave towards him as a dead man would. Ironically Feraud has been ‘dead’ to the world for years, lost in a grudge for so long that he’s no longer even clear about the reason it began. D’Hubert resumes his married life and Feraud is last seen, Napoleon-like, gazing out across a river and engrossed in the torment of his own personal St Helena, exiled from the one thing, the mindless vendetta, that made him feel alive.

The sheer lyricism of the film and the narrative élan that Scott controls represents heights he would rarely reach again post the 1980s, and given his recent propensity for bloated commercialism it’s a salutary reminder of his not inconsiderable talent to re-visit his beginnings here. There’s something to be said for the hungry artist striving to make do with rudimentary budgets and constraints and Scott gets incredible mileage from his cinematographer and art director, both of whom shared his background in commercials and who achieved incredible things on a shoe-string. The look of the film is every bit as inspired, poetic and authentic as Barry Lyndon which cost over 10 times as much to make. Scott himself came from an army family and the detail and feel of the military is convincing. The two leads who are superficially unsuited to the type of roles they perform are both excellent, their American-ness adds a certain detachment that benefits the narrative as they are a pair whose destiny fate has entwined, Kietel’s method intensity is particularly suited to his emotional and obsessed Feraud. The supporting cast of mainly experienced Brits is wonderful and weave their craft in ways wily old pro’s know how, invisible yet indelible in the fabric of the film.

Scott, it seems, tends to judge the success of his films by box-office returns, and as Paramount failed to promote or capitalise on The Duellists it lost money, but gave him a great calling card to Hollywood, and so with one eye on the success of Star Wars Scott next looked to space and the superb Alien was the result. Thankfully we can apply a different standard to success than merely a monetary one and conclude that The Duellists is simply one of the greatest films of a golden age.