Renoir, America and France - a river runs through it.

By Michael Roberts

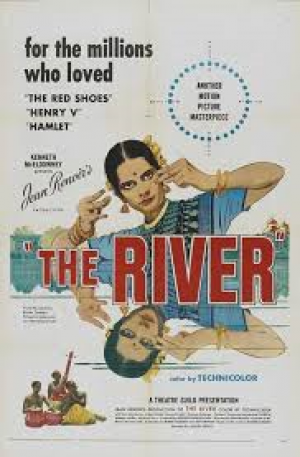

Exiled in Hollywood in the late 1940's, Jean Renoir struggled to get any projects realised at all, possibly because of the Hollywood Blacklist and his leftist political leanings, and eventually returned to France to continue his career. The bridging film between the two periods is the English language, American financed 'The River', shot on location in India and Renoir's first excursion into colour. A Hollywood florist, Kenneth McEldowney, who wanted to get into pictures, surprisingly provided the finance for the endeavour, and no less than Pandit Nehru's sister recommended he seek the rights for Rumer Godden's book of the same name. McEldowney discovered that Renoir had already optioned the book, and together the two began the long process of bringing it to the screen. Renoir had chased the rights after reading a glowing review of 'The River' in the New York Times, whereupon he immediately read it and was smitten enough to buy an option. Renoir and his team decamped to India for two years in order to do justice to the project, and produced one of the most glorious examples of colour film ever released.

The story is a simple coming of age tale of Harriet (Patricia Walters), a young upper middle-class British girl, living in India in the 1930's. A mysterious war veteran comes into the family's life, Captain John (Thomas Breen), and the young girl is smitten. Harriet's best friend is the slightly older Valerie, from a rich neighbouring family, and it's Valerie to whom John is attracted. The relationships become more tangled as John is also attracted to a mixed blood cousin, Melanie (Radha Burnier), who has no outward interest in the brooding ex-soldier. A family tragedy tips Harriet over into a cycle of despair, as she struggles to grow to womanhood amidst the beauty and squalor of a teeming Indian city.

Like all of Renoir's best work, 'The River' brims full of humanity and empathy. Renoir avoided the usual Indian film cliché's, "No tigers, no elephants, no Bengal Lancers", as he examined the life of a colonial family coming to terms with a changing environment. As political as he had been in America, supporting leftist and humanist organisations and working for the war effort, here Jean avoids the overtly political in favour of the intensely personal. By 1951, India had been through the wrenching change of Independence from Britain, and partition with Pakistan, but as the story is set in an earlier time (pre-WWII), the colonialism pictured here gives a telling taste of the cultural divide between the English and the locals. The serene beauty of the place she inhabits contrasts the confusion felt by Harriet in dealing with her raging hormones, intensified by the magnifying glass and bunker effect of her being an outsider in her own country.

Indian sexuality and it's temples adorned with erotic art confronted English prudery at every level. Renoir sees the earthy and easy sexual mores of the locals as a natural and beautiful thing, and he examines the gap between the colonial attitude and the local one via the character of Melanie, who's sexually charged dance stirs up the troubled ex-soldier. The hidden and psychological damage of war is alluded too, an issue all too pervasive in 1951, as are notions of heroism and valour, "Yesterday's hero is only a man with one leg". John is a damaged character, externally and internally, searching for a way to resolve his inner turmoil, "Where will you find a country of one legged men"? he's asked, and immediately the wider implications are felt, in that everyone needs to assimilate into the world they are in, rather than search Quixotically for a non-existent perfect world.

Melanie, caught between two worlds, craves acceptance as much as John and Harriet does, and represents the dilemma of the half-caste and of the colonial legacy. In the melting pot of post Colonial India, class and identity became even more complex, but ultimately Renoir alludes to the fact that such arbitrary barriers are not seen in nature, and facing up to and accepting people without judgement is a thing to be cherished. India, as shown by Renoir, is in many ways the embodiment of the Cobra, mesmerising the colonial masters but able to strike at any second. The English family, ironically disconnected from the land via the artificial compound they've built, further emphasising their outsider status, struggle to belong. The river as a powerful metaphor, eternal and unchanging, connecting one generation to another, connecting one race to another, is the great equaliser here, as is death, and Renoir evokes all the dimensions of the human existential question with deftness and care. The rituals and colour of India are boldly on show, underpinning the breathless and teeming humanity centred on the river.

Renoir used a mostly inexperienced cast, including some non-actors like Breen, which combined with the 2nd unit documentary style footage and location shooting gives the film a cinema verite feel. Possibly inspired by the Italian neo-realist success, which he himself had inspired in part, Renoir pulls all the elements together to create a coherent whole, but adds his own poetic flourishes to add an extra dimensionality. Renoir's first foray into colour set the standard for use of the medium, matching Michael Powell's 'The Red Shoes' in the pantheon of cinematic achievement. Jean could have been genetically blessed when painting with colour and light on screen, as his father Pierre- Auguste Renoir was one of the greatest painters to have ever lived, but his eye and taste on 'The River' is second-to-none. Renoir's visual flair thrived on the sub-continent, it's expansive vista's and smiling, vibrant faces drew even deeper into his naturally empathetic persona, and pulled a work of great art from him as a result. India's overwhelming humanity touched Renoir, in all it's contradictory glories, and he translates the feeling across the screen via Godden's intimate family saga.

Jean Renoir would return to Paris, reinvigorated by his Indian sojourn, to a period of nostalgic reflection with his colourful, theatrical cycle of films, 'The Golden Coach', 'Elena and her Men' and 'French Cancan'. 'The River' is Renoir painting his intimate and delicate rendering of the human condition on the sprawling canvas of India and her teeming millions, and his touch is able to accommodate and to hold in balance those competing elements. A master class in the use of colour and light, and a masterpiece of visual poetry from the greatest director who ever lived.