Bergman v God and The Joy (lessness) of Sex

By Michael Roberts

Angel v Animal - God, Sex, Love and Death! - Step right up.

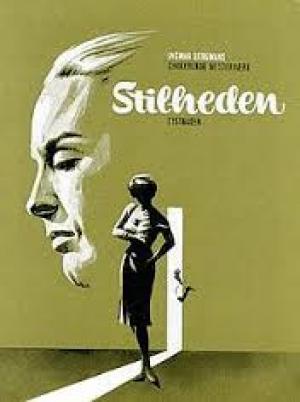

Ingmar Bergman was at the height of his powers and international reputation when he stepped up to make The Silence in 1963. In the three years prior he had already won two Academy Awards for Best Foreign Film (The Virgin Spring, Through a Glass Darkly) and had also produced Winter Light , a masterpiece that investigated Bergman’s alienation from his Lutheran faith. The Silence came to be regarded as a companion piece to the two preceding films, similar in bleakness of tone and forming a so-called Trilogy of Faith. Bergman originally titled the film God’s Silence, as he said it focused on spiritual issues but chose the final, less religious sounding title to evoke the difficulty of communication between humans without referring directly to the distant, silent heavens.

Two sisters, Ester (Ingrid Thulin) and Anna (Gunnel Lindblom), along with Anna’s son Johan (Jörgen Lindström) travel into an un-named foreign city and take rooms at an hotel. The veneer of civility between the two women strips away as it becomes apparent that both have very different world views, leaving Johan caught in the crossfire. The city seems to be on the brink of some unspecified military action, and the tension that creates, along with the language barrier, makes for a testing and sometimes nightmarish experience for the trio. Ester has an unspecified illness that seems to be life threatening, but while she struggles with health related issues in her room, a dolled up Anna hits the bars while Johan explores the old hotel.

Bergman investigates the age old divide between the immanent and the corporeal in this film, via the prism of the earthy Anna and the intellectual Ester. The ability to communicate is at the centre of the dilemma, which Bergman underscores by having the drama take place that is ‘foreign’ to the sisters. Anna takes a lover, much to Ester’s disgust, and Anna tells him, “how nice that we don’t understand each other,” echoing the situation she experiences with her sister.It is plain that the sisters do not speak each other’s language at all and that they may as well be conversing in a foreign tongue and Bergman examines this accident of birth that has inextricably linked two such different souls.

Language forms a key plank of Bergman’s essay on loneliness and human connection, where Ester values words and ideas above flesh and blood, voicing the traditional Lutheran contempt for “erections and secretions.” Ester is confronting her own mortality, “Dear God, please let me die at home,” as she clearly holds contempt for her decaying body, a common position of the aesthetes of Christianity. Ester is content to focus on the eternal and the pious, to the frustration of her lively sister who finds her means of escape in more earthly pursuits. Bergman presents a startling image of Ester masturbating, a provocative and controversial move in 1963, but it’s a scene devoid of sensuality or joy as Ester furiously attempts to escape from her own self loathing, only succeeding to add to it. The counterpoint is hardly a contrast as Anna’s own sexual escapades are also joyless and on the sad side of tawdry, devoid of connection or feeling.

Ultimately Bergman frames the struggle between the sisters as nothing less than a battle for Johan’s ‘soul’. Ester’s philosophy posits an ethereal connection to a nebulous God, arrived at through the higher disciples of language, prayer, thought and reflection. Ester attempts to instil a love of words into Johan, to bequeath to him her love of language, hoping it will lead to a curiosity and intellectual life far removed from her sister’s epicurean worldview. Bergman places the drama in an un-named European country with an impenetrable language, seemingly preparing for war. For all the tension and damage going on outside the hotel room Bergman seems to be suggesting that nothing a war can offer can come close to the damage we do to those close to us when passions flair and old wounds are opened.

The work or the two lead actresses, both members of Bergman’s stock company who had key parts in Winter Light, is simply flawless. Ingrid Thulin is devastating as the parsimonious Ester, a role requiring enormous range and control; she carries it off superbly and won the inaugural Best Actress at the Swedish Film Awards in 1964. Gunnel Lindblom brings an edgy presence to the role of Anna, an emotional cousin to the pivotal role she had of Ingeri in Bergman’s The Virgin Spring, the first of his Best Picture wins in 1960. Lindblom is very fine in the part of the less than intellectual sister in touch with her animal side while she struggles to raise her son, evidence of her ‘fall’ in the eyes of a misogynist Christian ethos. Håkan Jahnberg makes an impression as the elderly waiter, and his scenes with the young Jörgen Lindström are delicate and beautifully realised.

Bergman came to finally accept he’d made a coherent ‘trilogy’ that had examined his relationship to the faith of his childhood, being as he was the son of a Lutheran minister. He said later, "These three films deal with reduction. Through a Glass Darkly conquered certainty. Winter Light, penetrated certainty. The Silence, God's silence, the negative imprint. Therefore, they constitute a trilogy." Sven Nykvist shot the beautiful and spare images, maintaining the consistent style he brought to all his many collaborations with the master. The framing and depth of the hotel passageway sequences can be felt in Kubrick’s disturbing The Shining, another film with a young boy walking empty halls.

Bergman carved a place for himself as the premier existentialist filmmaker of his, or for that matter, any generation, unafraid to tackle the bigger questions that others shied away from. After this compelling trio of masterworks Bergman moved away from ruminations on God and man and concentrated on the solely inter-personal in seminal works like Persona and Cries and Whispers. If Winter Light is Bergman’s dark and sombre sonata in the key of bleak, then The Silence is a jarring, modernist collage of angular sounds, dissonant harmonies and clashing tones. Ingmar Bergman is simply a giant in world cinema, a genius whose influence is immeasurable and resonates through the decades still.