Words are flowing out like endless rain into a paper cup...

By Michael Roberts

“I say in speeches that a plausible mission of artists is to make people appreciate being alive at least a little bit. I am then asked if I know of any artists who pulled that off. I reply, 'The Beatles did'.”

~ Kurt Vonnegut

Beatle fanatic and writer Mark Stanfield created this conceit from the kernel of the actual meeting of John Lennon and Paul McCartney at The Dakota on the night Lorne Michaels offered The Beatles $3000 to get back together for a gig. As it happened Paul and Linda were visiting John and Yoko and watching Saturday Night Live, filmed just a few blocks away at Rockefeller Plaza, as Michaels lampooned the massive $200 million offer that Sid Bernstein had flouted for a Beatle reunion, and toyed with the idea of driving down and playing something. The idea fizzled and the pair stayed in, but the event caused Stanfield to concoct a ‘what if’, scenario, where the two men meet alone and discuss their incredible shared past and the hanging tension of issues still unresolved.

Paul McCartney (Aiden Quinn) is in New York to play as part of his band Wings, then on a world tour promoting their world wide number one album, Wings at the Speed of Sound. On a TV interview Paul is asked the inevitable question about the Beatles getting back together, which he answers with a non-committal “You never know”. Travelling back to his hotel suite Paul instructs the driver to take him to the Dakota on Central Park West, where he persuades the desk clerk to call John Lennon (Jared Harris) and announce “a visitor”. John lets Paul come up and they engage in an uneasy conversation about “You, me and everything between us”. They argue, laugh and go for a stroll through the park in disguise, and visit a small restaurant. They return to the Dakota, going up on the roof to smoke dope before they watch Saturday Night Live together, until a call from Yoko changes the mood and Paul leaves.

Both Harris and Quinn provide convincing characterisations of the famous duo, an acting job fraught with the danger of falling into cheap caricature. They adopt familiar mannerisms and manage fair Liverpudlian accents, no great leap for Harris perhaps, the son of acting legend Richard Harris, but a reasonable feat for American Quinn. Lennon and McCartney were so well known, possibly the most famous people on the planet in the 1960’s, that any false notes would help sink the fantasy, but remarkably the fictional extrapolation plays out with an engaging and enjoyable momentum as we watch the two old friends re-engage.

The film works best because of the simplicity of the concept, the elimination of all other voices so we can concentrate on the dynamic between the two, without wives and families and hangers on. The device allows Stanfield to unpack the residual issues between John and Paul, in the context of their post Beatle lives, of two men forever doomed to live in the massive shadow of their younger selves. The film is accurate in as much as there are no oddities or anachronisms regarding the references used, a tribute to the deep knowledge of the writer and also to his technical advisor, Beatle expert Martin Lewis who said, “I spent a lot of time working on the project. I dug up hours of film, video, TV and radio material of John and Paul so that Aidan and Jared could immerse themselves in the characters they were portraying. Much of the material was rare. What I especially wanted to give them were tapes of John and Paul talking when they were not ‘on’, but being themselves; as they obviously would be when the two of them were together without others around. We also spent hours discussing their characters and the dynamic of their relationship - Aidan and Jared were incredibly hard-working. They took their work very seriously. Neither of them planned to be impersonating their characters. They wanted to capture the essence of them more than anything.”

Stanfield and Lewis had the good fortune of having Michael Lindsay-Hogg direct the two-hander, and his intimate knowledge of the foibles of Lennon and McCartney gives the film a layer of authenticity that might otherwise have been lacking. Lindsay-Hogg (the biological son of Orson Welles no less!) was central to the Beatles TV output in the ‘60s, directing clips for Paperback Writer, Rain, Hey Jude and Revolution, as well as working with John on The Rolling Stones show, Rock and Roll Circus. He was then pressed into service to direct the unwitting visual document of four friends fracturing at the seams, the final Beatle feature film, Let It Be. He also worked with McCartney and Wings so his insight into the period and personalties was invaluable in lifting this conceit out of the realms of fan generated hagiography.

Lindsay-Hogg signed up because he wanted to explore the notion of a maturing and changing friendship surviving, albeit with a different tone, he said, it “wasn't so much about The Beatles. It was a very good script in which the agency of these two famous people and their story takes you somewhere deeper. To me, that's the nature of friendship: How we grow, how we grow up, and how things change. These boys knew each other when they were 16 and now they're 35 and they have to find a new truth. We all have our own relationships like that, whether they're matrimonial relationships or friendships.” The film unfolds with a delicate rhythm and tone, and as the arctic frost thaws an easy camaraderie emerges, which allows Lindsay-Hogg to make the most of via his subtle references to past (and future) events, as in the ‘rooftop’ scene here and the allusions to McCartney’s Japanese drug bust.

The tradition of a fantasy meeting between iconic individuals is an old one, recently well represented by Nicholas Roeg’s Insignificance, which shows a meeting between Marilyn Monroe, Joe DiMaggio, Joe McCarthy and Albert Einstein in the 1950’s. The conceit allows a writer to wax lyrical on all manner of things and to have it filtered through the voice of people that mean something in the popular imagination, and so it is with Lennon and McCartney. Their music defined a generation, and gave them lives that would have been unimaginable, born as war babies in the drab Northern England port town of Liverpool, before rock and roll showed them a way out. The core friendship of John and Paul was a key to the bands success, not only to the surfeit of remarkable and iconic songs that would be penned under the joint credit, but also their spark and energy. George Martin said he worked with them because he was drawn to them as people first, he thought their music was then not so good, and with George Harrison in tow they were an unbeatable triple act.

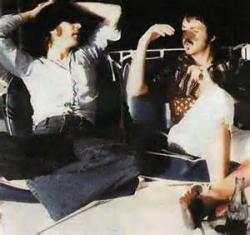

Lennon and McCartney’s music has meant so much to generations, its seemingly timeless appeal finds new fans every year, and yet there is none of it here. Ironically that was because the producers could not get Michael Jackson’s company to licence the tunes, and although it would have been nice to have them, the film works fine without them. The idea of the two men sorting out their differences this way is one with a justifiable appeal to fans - I can remember the moment I saw a photo of the two of them together as ex-Beatles and being markedly affected. They met in 1974 (actual shot on panel right - frame 6) in LA during John’s ‘lost weekend’, and the bootleg recordings of the jam session reveal just how lost they were, but to see that image 20 years after it was taken was emotional for me. There were never any photos of contact between the two of them and all we heard about was the ‘feud’, played out in public with snarky messages on each others albums. That image humanised the dilemma, but also represented a layer of hope, where we could now happily imagine some rapprochement had occurred.

Two of Us is no lazy exercise in nostalgia; it’s a complex take on a complex relationship, one that could only really be understood by the two people involved. This is why, quite wisely, there is a long disclaimer at the beginning to remind viewers that history is one thing and this fictionalised event is another. It’s done with respect and humour (even including Lorne Michaels’ arch aside that they were free to split the $3000 however they like, “you can pay Ringo less”) with two fine central performances, and it’s done with heart, and for that it is an unlikely but worthy addition to all things Beatles. Fab.

* There have been revelations some thirty years after the events of 1974 that reveal Paul's central role in getting John and Yoko back together. It transpires that during a visit by Paul and Linda in New York, Yoko told Paul she still loved John, then estranged and engaged in some highly self destructive behaviour with Harry Nilsson in LA. Paul then visited John and told him of Yoko's comments and of the conditions she'd set to take John back, which set the reconciliation in motion. John then returned to New York, still living with May Pang, and considered joining Paul in New Orleans to start writing together again, but when he moved back with Yoko shortly after, that plan fell away and Yoko re-established primacy in John's life.