This is a summer of discontent!

By Michael Roberts

Sometimes it takes an outsiders perspective to reveal something deep and profound about a country, think Billy Wilder in America, or more recently Ivory-Merchant in the UK, and so it is with the remarkable 1971 Australian film Wake in Fright. Canadian Ted Kotcheff directed a script by Evan Jones, a Jamaican born, American educated writer and starring English leads. The source novel was by Australian novelist Kenneth Cook, written in 1961, and originally the film was attached to Joseph Losey and Dirk Bogarde, with whom Evan Jones had a close working relationship as Losey’s preferred screenwriter in the early ‘60’s, having written the script for King and Country et al. Australian producers bought the Jones script and the film was made in 1971, with many key Australian actors in supporting parts, including Chips Rafferty and Jack Thompson.

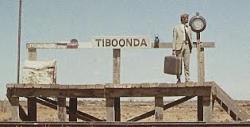

John Grant (Gary Bond) is a bonded school teacher, posted to a small outback town and chaffing at the bit to escape. Christmas holidays afford him a chance to return to Sydney for 6 weeks, via a train to Bundanyabba and a flight to the ‘big smoke’. After a series of misadventures in ‘The Yabba’, John becomes stranded and has to deal with the macho culture and oppressive heat and brutal rites of passage in order to survive at all.

Kotcheff and cinematographer Brian West capture the space and threat of the outback perfectly, from the beautiful panning shot that opens the film to the bookend equivalent that ends it. The film operates at the level of a western; John is a ‘tenderfoot’ who wanders into a frontier town and goes through a series of male-centric rituals, drinking, gambling and shooting, in order to prove his worth. He is also the classic ‘schoolmarm’ character, essentially feminine, underlined by his empathy and connection to Janet (Sylvia Kay), the girl trapped in the middle of the macho maelstrom. It also allows a homo erotic subtext between the lecherous and libidinous Doc (Donald Pleasance) to insinuate itself into the denouement. “Sex is just like eating, it’s a thing you do because you have to, not because you want to, but most people are afraid of it” says Doc. John feels empathy for Janet, who is a victim of the culture and merely seeking her escape in her own ways. Doc plays his mind games with John, putting him right about the reach of Janet’s activities to alleviate the grinding boredom, and Janet subtly admits as much when she’s assessing a pregnant dog, “She’s a slag this little mutt, she’d try anything”.

John’s “puritan’ ethos is pilloried by Doc and challenged by the local rites, embodied by the boorish and ‘yobbo’ behaviour of Dick (Jack Thompson) and his friends. John strains at the demands of the “aggressive hospitality” he encounters, which is summed up in his bitter final speech, “I can rape your kids, that’s ok, but refuse to have a beer with you and it’s the worst thing in the world”! Doc disavows John of any misconceptions of the rawness of life on the edge of nowhere, an abyss that John is in danger of falling into. The edge is usually taken off by sardonic humour, a cabbie mentions to John “We have a lot of suicides, it’s the heat”, to which John replies, “That’s one way of getting out of town”. Doc also gets in on the act, telling John why he came to the Yabba, “I’m an alcoholic, a disease which prevented me from practicing in Sydney but out here it’s scarcely noticeable”.

The strength of the support cast gives a fine and authentic canvas of types to populate the screen, some broadly painted but not to the point of caricature. Chips Rafferty is wonderful in his last film appearance and Jack Thompson fine in his first. Gary Bond is effective as the fish-out-of-water John, and feels like an authentic and effete ‘60’s Australian urban type, essentially indistinguishable from certain Englishman. Wake in Fright came in an era where Australian accents were becoming more common on screen, as prior to this most Australian film and TV actors spoke in the plumy tones of BBC newsreaders. The acting honours belong firmly with Donald Pleasance, who provides a stunning and unforgettable performance as Doc. The theatre trained Englishman attacks the role with relish, fleshing him out in every gritty detail and even managing a note perfect Australian accent.

Wake in Fright has none of the politeness of most of the Australian cinema that preceded it, and it speaks to the influences of the honesty of the British New Wave and the surge of energy American film experienced on the back of the Nouvelle Vague. It is not a pretty film, and is confronting at every level, not least in the actual kangaroo shoot, a brutal and ugly event that sickened the film crew. Kotcheff managed to convey the nightmare tones of the novel, and to provide a record of a time and place that scandalised Australian audiences, appalled at seeing the rawness of outback behaviour laid bare. That macho ethos still dominates many inland towns, like Broken Hill, the remote NSW town that stood in for the Yabba, even if modern connectivity has mitigated some of the isolation that fed the discontent.

Ted Kotcheff did not go on to maintain the standard he reached here, and the producers of Wake in Fright were better known for family TV shows than cutting edge cinema, but for one time at least they got it absolutely right. Wake in Fright was a marker for the cutting loose of the ‘cultural cringe’, the idea that nothing of quality could be produced by and for Australians, that Australians did not have an authentic voice, and it was a sign post for the way ahead embraced by the New Wave directors of the later ‘70’s revival. The film is a quintessential Australian film, no matter its disparate inputs, and stands as a remarkable achievement in any era.