An outsider Outback

By Michael Roberts

Nicolas Roeg followed his co-directional debut film, 'Performance', with a trip to Australia and an exploration of the ancient rites of the Aborigine as contrasted against the white urban experience. Roeg elected to shoot the film himself, his credentials established as a successful cinematographer on films such as Truffaut's 'Farenheit 451', Schlesinger's 'Far From the Madding Crowd' and 'Petulia', and 'Performance'. The Australian landscape offered an epic canvas for Roeg to work with as every direction he pointed his lens found something interesting or extreme to linger on, and like many outsiders he uncovered an Australia it's inhabitants barely recognised. Roeg cast his young son Luc as the boy, billed as Lucien John, and Jenny Agutter as his older sister, and gave young aborigine David Gulpilil his first significant role before he went on to be a fixture on local screens.

Roeg opens on a close up of a city brick wall, all formal lines and order, before presenting a collage of city images, showing Sydney to be a bustling metropolis. An office worker (John Meillon) walks out of Australia Square, a modern and angular structure reminiscent of Tati's 'Playtime' buildings, and returns home to his middle class apartment on Sydney Harbour. His two children, a daughter of 16 and a son aged 6, come home from their expensive private schools and swim in the pool, while mum prepares dinner. Roeg then takes us into the Outback, where the father and his two children are sitting in a car in the middle of nowhere, they are in their school uniforms and he has a picnic ready. All is not what it seems however, as Dad unravels and the children flee, getting lost in the deep bush before they encounter a young Aboriginal boy on walkabout, an initiation for young men. The young man helps the white children find their way out of the inhospitable terrain, while he deals with his initiation in the harsh environment.

One can only imagine that the wide-open spaces of the Australian outback represented another world for an Englishmen like Roeg. He avoids any geographical niceties, like the fact that the picnic takes place at least two days drive out of Sydney, favouring action over exposition and impressionism over overt explanation. Juxtaposed against the visual form of the city, the ordered and structured buildings and machinery is the chaos and emptiness of the interior, and the random attempts to tame the wilderness through white settlement. Contrasted against the order and rigour of the school classroom is the easy grouping of a band of itinerant Aborigines, embracing their environment rather than setting themselves outside of it. Several visual montages counterpoint the modern world with the ancient, none more so than the hunters who cut a swathe through the bush killing wildlife wherever they encounter it, after we've seen the Aboriginal boy hunting with spear, throwing stick and boomerang.

Roeg's collision of modern and ancient weaves around the mystery of the unexplained personal crisis that leaves the boy and girl stranded in the desert. Roeg uses diegetic sound to underscore the breakdown the father suffers, having the portable radio provide the soundtrack. In the case of the father's breakdown, he prepares the burning of the car to Rod Stewart's 'Gasoline Alley'. As night falls for the first time on the children, they tune in to a radio debate about the end of the world, "society will come to an end", so it's possible to read the father's murder-suicide intentions as that of a man not wanting his children to face a nuclear Armageddon. At various points throughout the narrative Roeg intercuts one type of action with another, contrasting approaches and realities. The Aborigine hunting his kangaroo meat is broken up with shots of a city butcher chopping up meat, a scene where some meteorological workers are at a camp, ogling the legs and breasts of the only woman in the group is set against the burgeoning sexual awareness of the girl in relation to the young black man's body.

Roeg suggests that the children's preparation via their schooling leaves them ill equipped to survive in the wilds of the Outback, and soon falter once the comforts of the city fade. The Aborigine boy saves them, yet they remain frustratingly close to white civilisation, (the Aborigine converses with a white woman, out of their sight, at one point) and they remain unaware because of the language barrier. The girl connects with the experience as she grows comfortable in the ability of the boy to provide for the group, and she immerses herself in the experience in unexpected ways by connecting with the land. The traditional Aboriginal philosophy is one of custodianship, not ownership, and they see their time upon the land as transitory, just a link in the chain it's beholden upon them to pass it to the next generation in good shape. White civilisation commenced in Australia with the disgraceful legal fiction of Terra Nullius, i.e that the land was not occupied by anyone who could be identified as traditional owners of the property. The High Court overturned the doctrine in law in 1992 with the Mabo decision, but a stand-off still remains about native title being read in concert with freehold (white) title.

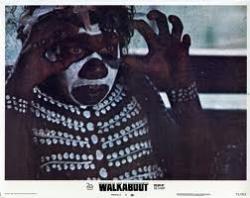

Roeg's film is a meditation on progress, yet he mostly avoids the 'noble savage' view of history by simply showing the young Aboriginal man going about his business with no artifice or fuss. David Gulpilil delivers a wonderfully droll and straightforward performance as he incorporates these two inept white children into his walkabout ritual. Roeg shows him to be a boy becoming a man, and his mating dance for the girl is a great way of showing the differences and the shared desires of the two adolescents coming to terms with their nascent sexuality. Jenny Agutter proved herself a capable actress after emerging from her child actor phase, and invests great nuance into her portrayal of the lost 'English' girl, a stranger in her own land. The final image of her chained to the same middle class domestic life as her mother's, as she wistfully conjures up an imagined paradise in an Outback gorge is beautiful and heartbreaking.

'Walkabout' delivers on every front, it's a commercial art film, poetic and lyrical, engrossing and absolutely alive to the world it depicts. Like the Candadian director Ted Kotcheff, who memorably essayed white Australian macho bush culture in 'Wake in Fright' the same year, Roeg has an independent and clear-eyed view of the country, devoid of any grovelling nationalism, and one that holds up today. Roeg would enter a particularly fertile phase after this film, one that saw the undoubted masterpieces 'Don't Look Now' and 'The Man Who Fell To Earth' produced, before falling prey to a patchiness in the 1980's and beyond.